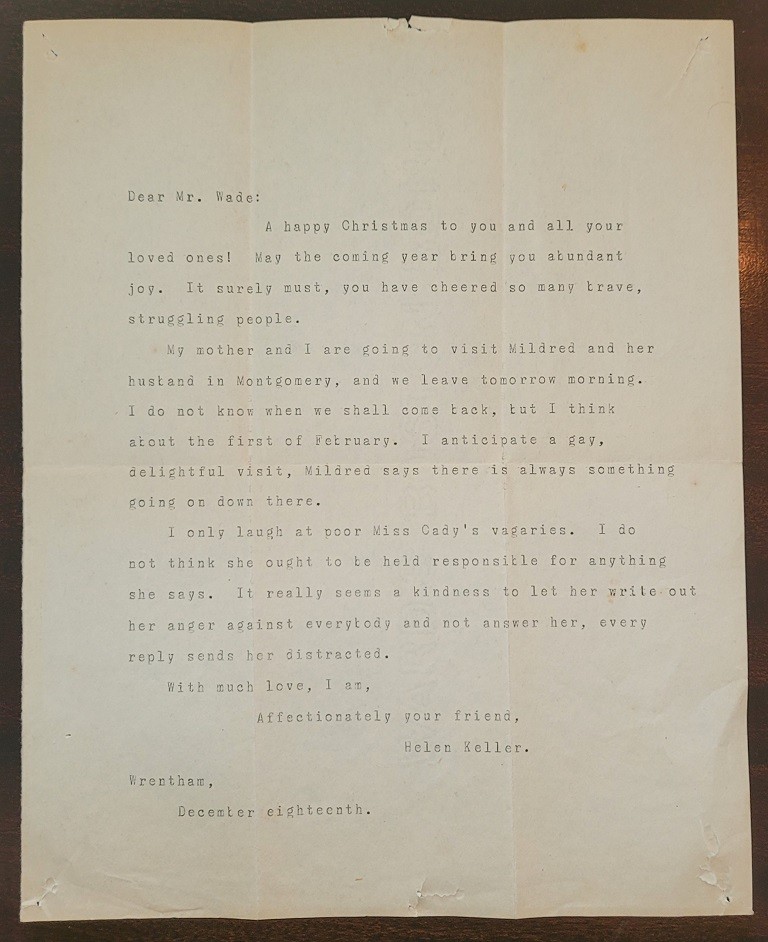

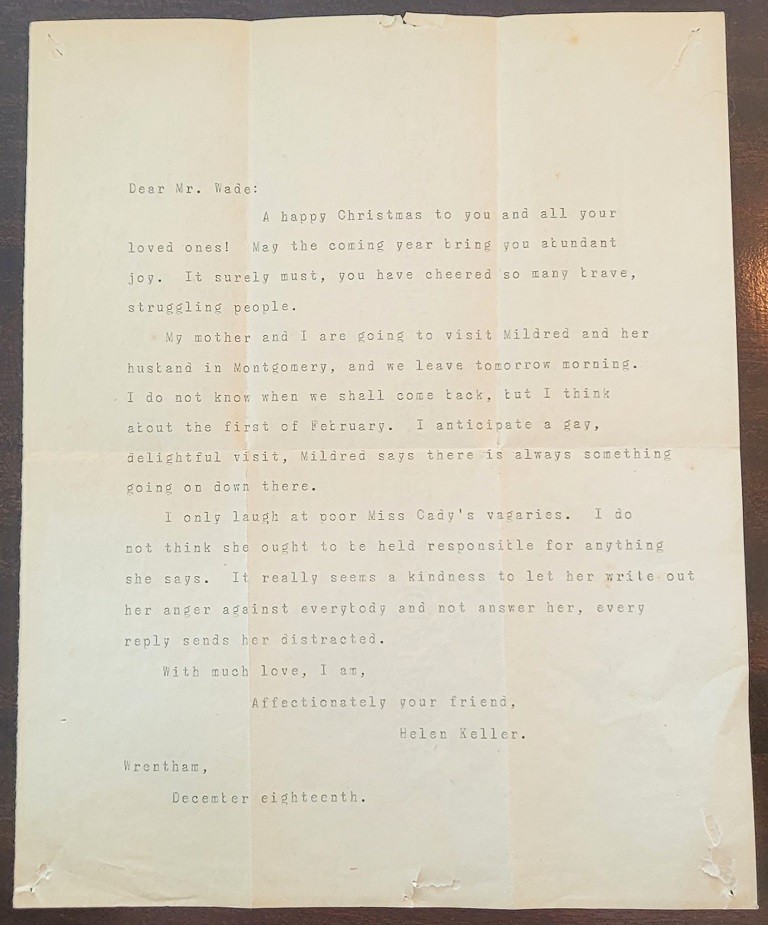

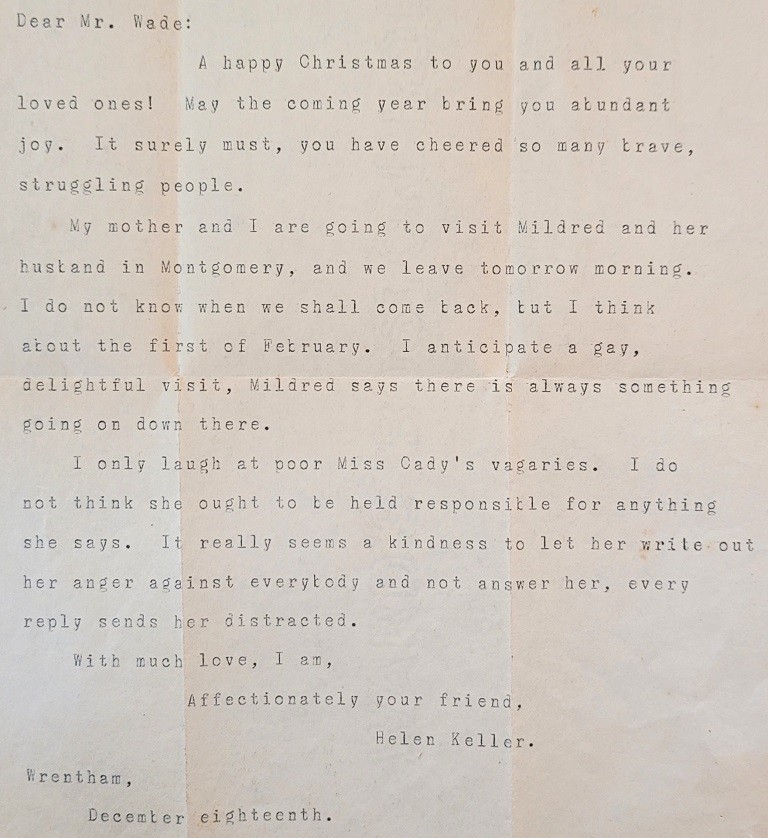

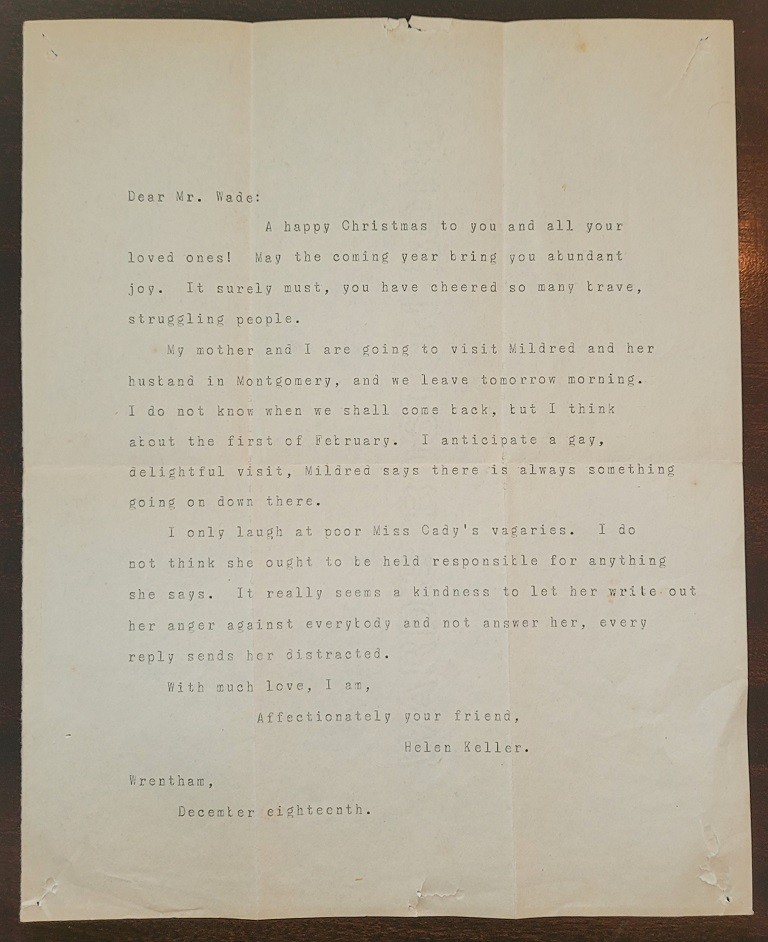

Helen Keller Letter to William Wade dated 18 Dec 1901

PRESENTING A VERY IMPORTANT AND HISTORICALLY SIGNIFICANT Helen Keller Letter to William Wade dated 18 Dec 1901.

This is a fully typed letter from Helen Keller and unfortunately is not personally signed BUT it is the content that is simply ‘EXPLOSIVE’ and ‘HUGELY SIGNIFICANT’.

The letter is not fully dated, namely, the year it was written, is not noted.

When we first read this and in particular the content of the final paragraph, we were ‘blown away’. The reference to “Miss Cady”, immediately made us think of ‘Elizabeth Cady Stanton’. If it is, in fact, referring to her, then the feelings/opinion, of Helen towards her at that point in time are indeed, very revealing! Clearly, ‘Miss Cady’ is elderly, probably suffering from dementia and ‘lashing out’ at everyone.

We are 100% certain that this letter is fully authentic. It was given by William Wade to Eliza Calvert Hall Obenchain (noted author, women’s rights advocate and suffragist), together with another letter from Helen Keller to him dated 20 Feb 1910 (listed separately) which references Eliza’s book, ‘The Land of Long Ago’, with a personal hand-written inscription thereon, from William Wade to Eliza stating “You may keep this if you wish. WW”.

We obtained these Keller Letters from the Estate of Eliza Calvert Hall Obenchain together with other fully authenticated letters from such notables as President Teddy Roosevelt, etc. These letters were kept in the family ownership until now.

Link: https://rockwellantiquesdallas.com/helen-keller-letter-to-william-wade-dated-20-feb-1910/

This letter has really led to us a ‘merry dance’, in attempting to identify the year it was written. It raises all kinds of questions. We have spent many, many hours conducting research to try and identify the year. The questions it raises are a real ‘conundrum’ for the following reasons:

(1) Helen Keller and William Wade were good friends and Helen considered him a ‘father figure’ and ‘mentor’. In 1899 they had a ‘falling out’ which is recorded in a letter from Helen to him in 1899 (contained in the Library of Congress) where she accuses him of betrayal of her trust. When William died, in 1913, Helen gave his Tribute in his Obituary and referenced their falling out as: “Circumstances and a grave misunderstanding brought about by meddlesome persons whom he trusted had separated us for about four years. But at last he understood what had happened, and he came back to me, and that was a happy day for us both. I still feel the warm pressure of his hand when he bade me goodbye, saying: “Never forget me, Helen. Always write to me when I can help you.” He was truly one of the best friends I ever had, and one of the best men that ever lived.” So, surely this letter must be post-1903???

(2) Helen references in the second paragraph that she and her mother are travelling to Montgomery, Alabama to visit her younger sister Mildred and her husband. This led to us researching Mildred. Mildred was born in 1886 in Montgomery and her marriage, death and burial details show that she was married to Laban Warren Tyson in 1907. She is buried with him and her gravestone refers to her as ‘Mildred Keller Tyson’ BUT she was also known as ‘Mildred Campbell Keller Tyson’ on various records. So where did the name ‘Campbell’ come in??? From our research we discovered that Mildred was in fact previously married to a man named ‘NN Campbell’. No proper records exist for this marriage or the reason for it’s dissolution. Were they divorced or did Mr. Campbell pass away? In 1901, Mildred would only have been 14/15 years old, so surely, she was too young to be married??? BUT in 1901, it was not unusual for girls this age to get married and in some States the age limit was as low as 12 years old for girls. So it is entirely plausible that Mildred was married to Mr Campbell in 1901.

(3) Is the “Miss Cady’ referenced in the letter actually ‘Elizabeth Cady Stanton”? She died in October 1902, and if she is the person referred to herein and is clearly still alive and living out her “vagaries” then surely the letter being dated 18th December must be 1901? It is possible that it could have been 1902 and both Helen and William, had not yet heard of the death of ‘Miss Cady’ 2 months previously, BUT I doubt that! The passing of Elizabeth Cady Stanton would have been national news and especially amongst the Women’s Rights and Suffrage Movements of which both William and Helen were deeply involved.

So, IN CONCLUSION, this letter MUST have been written at the end of 1901 before the death of Miss Cady and is correcting a number of historically recorded issues, namely, (1) the falling out between Helen and William was only for a couple of years and not 4 (2) her sister Mildred was married at 14/15 years of age but that marriage did not last and (3) Miss Cady was obviously corresponding with William Wade and ‘lashing out’ at everybody, hence Helen’s observation that it was best to ignore her.

(PERSONAL NOTE: Is it possible that Miss Cady was one of the ‘meddlesome persons” referred to by Helen in her Tribute in 1913? If she was … then the earlier resurrection of Helen and William’s friendship makes sense.)

William Wade (1883-1913) was a philanthropist living in his estate in Hulton, PA. He was an advocate for blind/deaf people, women’s rights and the suffrage movements. He authored and wrote the significant book ‘The Deaf-Blind’ in 1904. He met Helen Keller as a young girl in 1888 when Helen and her teacher Annie Sullivan travelled to visit him at his estate in PA. This meeting led to a lifelong friendship between the pair (with one minor disagreement) referred to above.

Helen Adams Keller (June 27, 1880 – June 1, 1968) was an American author, disability rights advocate, political activist and lecturer. Born in West Tuscumbia, Alabama, she lost her sight and her hearing after a bout of illness when she was 19 months old. She then communicated primarily using home signs until the age of seven, when she met her first teacher and life-long companion Anne Sullivan. Sullivan taught Keller language, including reading and writing. After an education at both specialist and mainstream schools, Keller attended Radcliffe College of Harvard University and became the first deafblind person to earn a Bachelor of Arts degree.

Keller worked for the American Foundation for the Blind (AFB) from 1924 until 1968. During this time, she toured the United States and traveled to 35 countries around the globe advocating for those with vision loss.

Keller was also a prolific author, writing 14 books and hundreds of speeches and essays on topics ranging from animals to Mahatma Gandhi. Keller campaigned for those with disabilities, for women’s suffrage, labor rights, and world peace. In 1909, she joined the Socialist Party of America. She was a founding member of the American Civil Liberties Union.

Keller’s autobiography, The Story of My Life (1903), publicized her education and life with Sullivan. It was adapted as a play by William Gibson, and this was also adapted as a film under the same title, The Miracle Worker. Her birthplace has been designated and preserved as a National Historic Landmark. Since 1954 it has been operated as a house museum and sponsors an annual “Helen Keller Day”.

Keller was inducted into the Alabama Women’s Hall of Fame in 1971. She was one of twelve inaugural inductees to the newly founded Alabama Writers Hall of Fame on June 8, 2015

Link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Helen_Keller

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (née Cady; November 12, 1815 – October 26, 1902) was an American writer and activist who was a leader of the women’s rights movement in the U.S. during the mid- to late-19th century. She was the main force behind the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, the first convention to be called for the sole purpose of discussing women’s rights, and was the primary author of its Declaration of Sentiments. Her demand for women’s right to vote generated a controversy at the convention but quickly became a central tenet of the women’s movement. She was also active in other social reform activities, especially abolitionism.

In 1851, she met Susan B. Anthony and formed a decades-long partnership that was crucial to the development of the women’s rights movement. During the American Civil War, they established the Women’s Loyal National League to campaign for the abolition of slavery, and they led it in the largest petition drive in U.S. history up to that time. They started a newspaper called The Revolution in 1868 to work for women’s rights.

After the war, Stanton and Anthony were the main organizers of the American Equal Rights Association, which campaigned for equal rights for both African Americans and women, especially the right of suffrage. When the Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was introduced that would provide suffrage for black men only, they opposed it, insisting that suffrage should be extended to all African Americans and all women at the same time. Others in the movement supported the amendment, resulting in a split. During the bitter arguments that led up to the split, Stanton sometimes expressed her ideas in elitist and racially condescending language. In her opposition to the voting rights of African Americans Cady was quoted to have said, “It becomes a serious question whether we had better stand aside and let ‘Sambo’ walk into the kingdom first.” Frederick Douglass, an abolitionist friend who had escaped from slavery, reproached her for such remarks.

Stanton became the president of the National Woman Suffrage Association, which she and Anthony created to represent their wing of the movement. When the split was healed more than twenty years later, Stanton became the first president of the united organization, the National American Woman Suffrage Association. This was largely an honorary position; Stanton continued to work on a wide range of women’s rights issues despite the organization’s increasingly tight focus on women’s right to vote.

Stanton was the primary author of the first three volumes of the History of Woman Suffrage, a massive effort to record the history of the movement, focusing largely on her wing of it. She was also the primary author of The Woman’s Bible, a critical examination of the Bible that is based on the premise that its attitude toward women reflects prejudice from a less civilized age.

Link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elizabeth_Cady_Stanton

Helen Keller Letter to William Wade dated 18 Dec 1901

Provenance: From the Estate of Eliza Calvert Hall

Condition: Very good. Some pin marks in the corners, minor tears on edges and corners as is evident from pics. Some fold lines. Some yellowing and fading of paper and type but not significant. Stored in plastic acid free bag.

Dimensions: 10″x 8″

SALE PRICE NOW: $10,000