Pair of Gainsborough Library Chairs in the Irish Georgian Style

PRESENTING A GORGEOUS and INTRIGUING Pair of Gainsborough Library Chairs in the Irish Georgian Style.

Made of walnut, probably in the 1980’s and probably made and upholstered in the US ….. for the ‘amusing and ironic’ reasons, we will ‘delve’ into later in this posting!

This pair of beautiful re-production chairs, were styled upon “Gainsborough’ Library Armchairs, from the Georgian Era of British & Irish furniture.

This pair were specifically styled on the ‘Irish’ Georgian Style, with the ‘hairy paw’ feet and the ‘Celtic Knot” motif on the armrests. Both motif’s being, ‘synonymous’, with Irish Georgian furniture in the mid to late 18th Century!

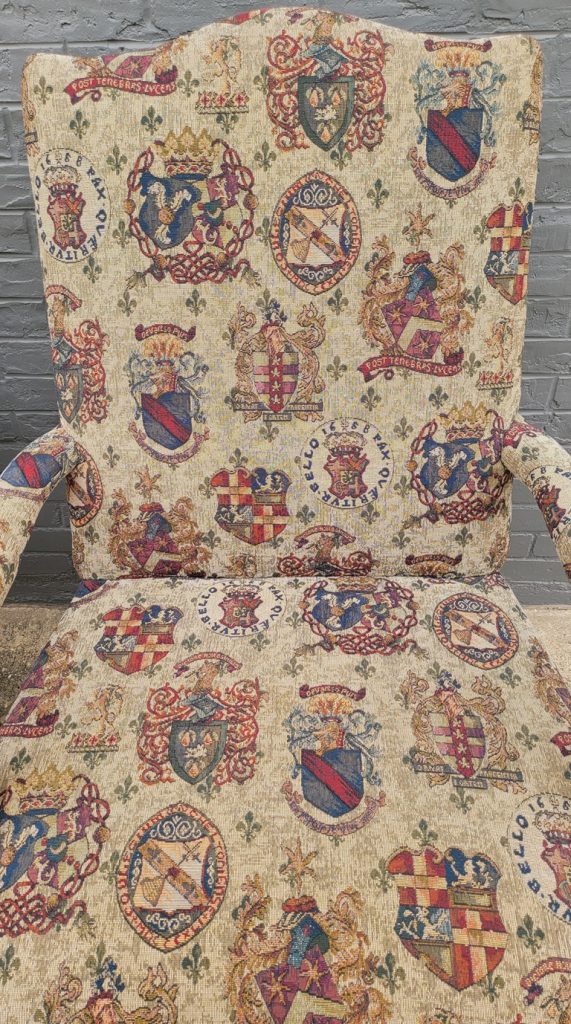

Both are upholstered in an antique style, ‘Coat of Arms’, tapestry style fabric, with various family ‘Coats of Arms’ or ‘Crests’ and family ‘Motto’s’ displayed.

The chairs each sit, on 4 curved legs, with acanthus winged armorial style central medallions on each leg’s knee and classic “hairy paw’ feet on all 4 feet.

When we first saw these chairs, we immediately identified them as good quality, reproduction Irish Georgian style chairs, but were ‘intrigued’ by the upholstery.

It looks like the upholstery is ‘original’ to the pair!

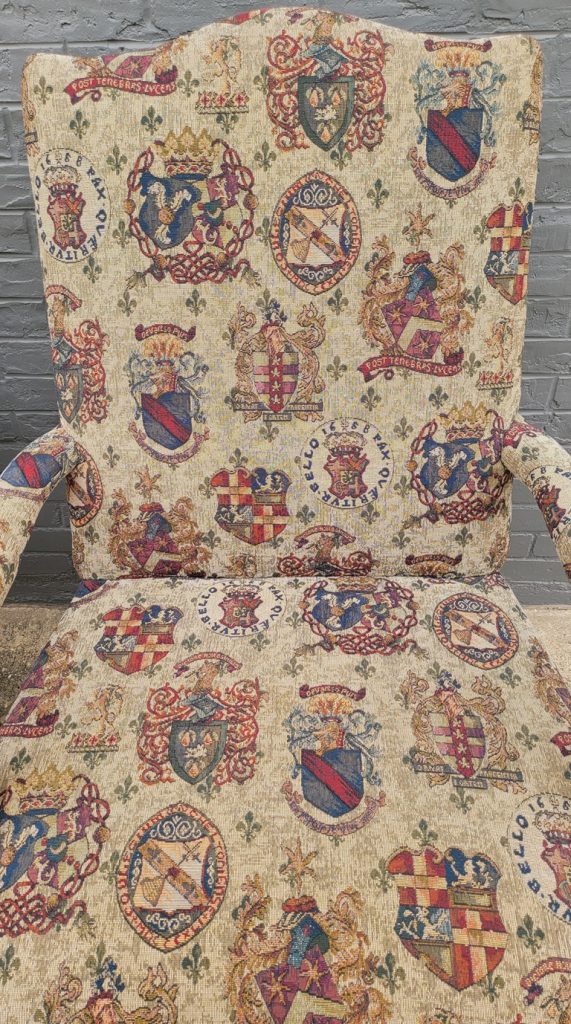

Initially, we assumed that these might have been ‘Irish-made’ in the mid to late 20C, BUT, then we researched the most prominent Crest/Coat of Arms and Motto on the fabric, namely, the one that has an armorial shield under crown with lion passant in the center and the flags of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales in 4 sections. Inserted into a circle, with the Motto: ” Pax Quaeritur Bello 1658,”

Much to our ‘initial shock’ and then ‘amusement’, this Crest & Motto are the family Crest/Coat of Arms & Logo of the ‘infamous’ …. “Sir Oliver Cromwell”!!!

“Cromwell’ is without doubt, the ‘most loathed and reviled figure’, (to most Irish people) in Irish history!

There is simply … NO WAY …. that an ‘Irish’ person, would put this fabric on an Irish chair …unless they had a very ‘twisted’ sense of humor …. like us! LOL

Therefore, these chairs must have been made in the US and upholstered with fabric that simply looked ‘historic’ and from ‘the Old Country’, with a complete lack of knowledge of the ‘historical significance and irony’!!!

This choice of fabric, coupled with the style of chair being “Irish’ … makes these chairs a ‘REAL CONVERSATION’ pair of pieces, as well as being extremely decorative, comfortable and useful Library chairs!

Imagine inviting your “Irish’ friends over, for a whiskey and having them sit on these chairs. Then telling them, that they having been sitting on Oliver Cromwell’s Coat of Arms! After their initial reaction, you can then ‘lessen’ the perceived indignity, by pointing out to them, that they have been resting their ‘posteriors’ on his symbol!! We told you, we had a ‘twisted’ sense of humor!! LOL

We simply could not resist getting them!

They are both in great condition, with no tears to the fabric and little damage or fading through normal wear and tear and age.

They have both been professionally cleaned.

A Gainsborough chair (also known as a Martha Washington chair in the United States) is a type of armchair made in England during the eighteenth century. The chair was wide, with a high back, open sides and short arms, and was normally upholstered in leather.

Gainsborough Chairs were designed and created during the George II era. They were named after Thomas Gainsborough, a British portraitist and artist who utilized the chair in having people pose for portraits.

The comfortable chair was undoubtedly great when helping Gainsborough’s subjects take poses for substantially longer. Gainsborough chairs had other names, including the French Chair as named by Thomas Chippendale.

Regardless of its name, the Gainsborough chair is incredibly comfortable and suitable you the living room or library. They work well in pairs, but that doesn’t mean having one isn’t good enough.

Gainsborough chairs are simplistic and yet have some impressive features. The chair was designed and created by Giles Grendey, becoming an iconic emblem of Gainsborough portraits. Here are some of the chairs’ features:

- Rectangular leather-upholstered backrest, which is cleverly curved to the shape of the back

- Outswept upholstered armrests with carved supports with acanthus decorations

- A square upholstered seat

- Cabriole legs with intricate carvings of an acanthus bracket with a flower head

- A rail with inscriptions of the designer’s initials

- Made from rosewood, mahogany, or walnut

- Open armrest sides

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 1599 – 3 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in the history of the British Isles. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially as a senior commander in the Parliamentarian army and latterly as a politician. A leading advocate of the execution of Charles I in January 1649, which led to the establishment of The Protectorate, he ruled as Lord Protector from December 1653 until his death in September 1658. Cromwell remains a controversial figure due to his use of the army to acquire political power, and the brutality of his 1649 campaign in Ireland.

Cromwell led a Parliamentary invasion of Ireland from 1649 to 1650. Parliament’s key opposition was the military threat posed by the alliance of the Irish Confederate Catholics and English royalists (signed in 1649). The Confederate-Royalist alliance was judged to be the biggest single threat facing the Commonwealth. However, the political situation in Ireland in 1649 was extremely fractured: there were also separate forces of Irish Catholics who were opposed to the Royalist alliance, and Protestant Royalist forces that were gradually moving towards Parliament. Cromwell said in a speech to the army Council on 23 March that “I had rather be overthrown by a Cavalierish interest than a Scotch interest; I had rather be overthrown by a Scotch interest than an Irish interest and I think of all this is the most dangerous”.

Cromwell’s hostility to the Irish was religious as well as political. He was passionately opposed to the Catholic Church, which he saw as denying the primacy of the Bible in favour of papal and clerical authority, and which he blamed for suspected tyranny and persecution of Protestants in continental Europe. Cromwell’s association of Catholicism with persecution was deepened with the Irish Rebellion of 1641. This rebellion, although intended to be bloodless, was marked by massacres of English and Scottish Protestant settlers by Irish (“Gaels”) and Old English in Ireland, and Highland Scot Catholics in Ireland. These settlers had settled on land seized from former, native Catholic owners to make way for the non-native Protestants. These factors contributed to the brutality of the Cromwell military campaign in Ireland.

Parliament had planned to re-conquer Ireland since 1641 and had already sent an invasion force there in 1647. Cromwell’s invasion of 1649 was much larger and, with the civil war in England over, could be regularly reinforced and re-supplied. His nine-month military campaign was brief and effective, though it did not end the war in Ireland. Before his invasion, Parliamentarian forces held outposts only in Dublin and Derry. When he departed Ireland, they occupied most of the eastern and northern parts of the country. After he landed at Dublin on 15 August 1649 (itself only recently defended from an Irish and English Royalist attack at the Battle of Rathmines), Cromwell took the fortified port towns of Drogheda and Wexford to secure logistical supply from England. At the Siege of Drogheda in September 1649, his troops killed nearly 3,500 people after the town’s capture—around 2,700 Royalist soldiers and all the men in the town carrying arms, including some civilians, prisoners and Roman Catholic priests. Cromwell wrote afterwards:

I am persuaded that this is a righteous judgment of God upon these barbarous wretches, who have imbrued their hands in so much innocent blood and that it will tend to prevent the effusion of blood for the future, which are satisfactory grounds for such actions, which otherwise cannot but work remorse and regret

At the Siege of Wexford in October, another massacre took place under confused circumstances. While Cromwell was apparently trying to negotiate surrender terms, some of his soldiers broke into the town, killed 2,000 Irish troops and up to 1,500 civilians, and burned much of the town.

After taking Drogheda, Cromwell sent a column north to Ulster to secure the north of the country and went on to besiege Waterford, Kilkenny and Clonmel in Ireland’s south-east. Kilkenny put up a fierce defence but was eventually forced to surrender on terms, as did many other towns like New Ross and Carlow, but Cromwell failed to take Waterford, and at the siege of Clonmel in May 1650 he lost up to 2,000 men in abortive assaults before the town surrendered.

One of Cromwell’s major victories in Ireland was diplomatic rather than military. With the help of Roger Boyle, 1st Earl of Orrery, he persuaded the Protestant Royalist troops in Cork to change sides and fight with the Parliament. At this point, word reached Cromwell that Charles II (son of Charles I) had landed in Scotland from exile in France and been proclaimed King by the Covenanter regime. Cromwell therefore returned to England from Youghal on 26 May 1650 to counter this threat.

The Parliamentarian conquest of Ireland dragged on for almost three years after Cromwell’s departure. The campaigns under Cromwell’s successors Henry Ireton and Edmund Ludlow consisted mostly of long sieges of fortified cities and guerrilla warfare in the countryside, with English troops suffering from attacks by Irish toráidhe (guerilla fighters). The last Catholic-held town, Galway, surrendered in April 1652 and the last Irish Catholic troops capitulated in April 1653 in County Cavan.

In the wake of the Commonwealth’s conquest of the island of Ireland, public practice of Roman Catholicism was banned and Catholic priests were killed when captured. All Catholic-owned land was confiscated under the Act for the Settlement of Ireland of 1652 and given to Scottish and English settlers, Parliament’s financial creditors and Parliamentary soldiers. Remaining Catholic landowners were allocated poorer land in the province of Connacht.

Link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oliver_Cromwell

Pair of Gainsborough Library Chairs in the Irish Georgian Style

Provenance: From a Dallas Estate

Condition: Very Good original condition (see full listing).

Dimensions: Each Chair is:

44.5 inches Tall, 34 inches Deep and 32 inches Wide

Seat Height is 19.5 inches; Seat Cushion is 26.5 inches wide at front.

Depth of seat Cushion is 22 inches; Armrests are 26.5 inches tall from the floor

SALE PRICE NOW: $6,000 (PAIR)