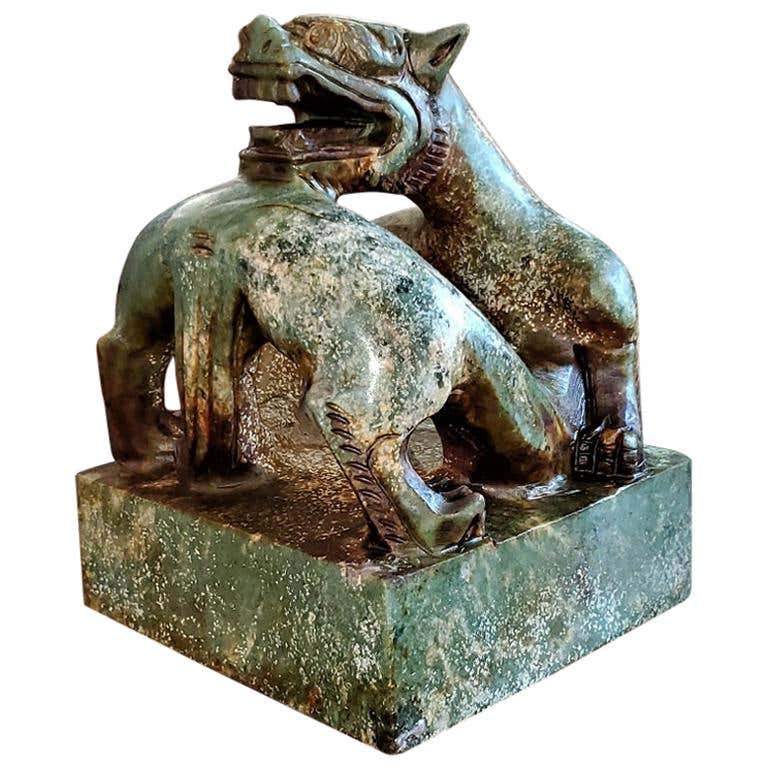

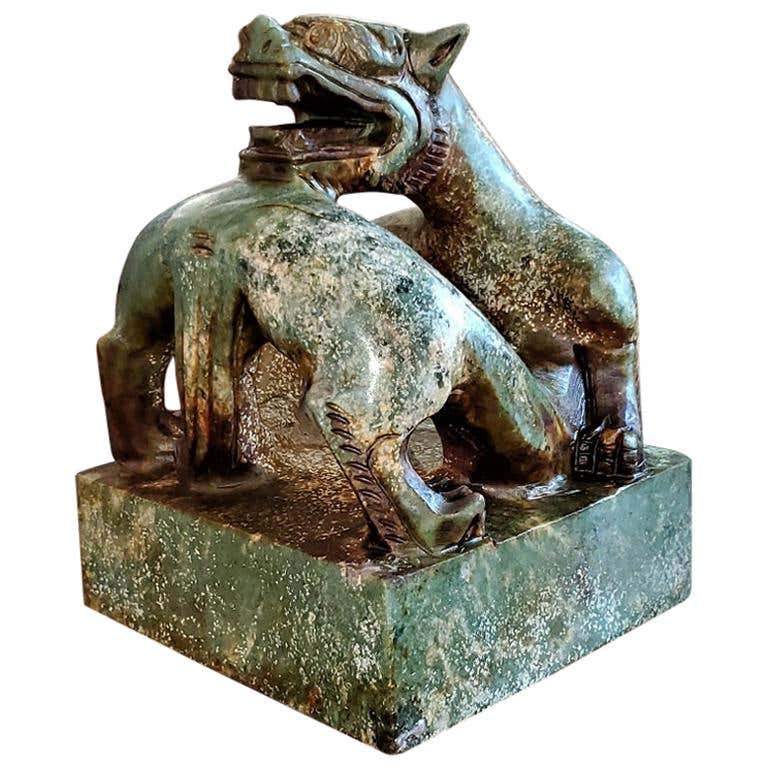

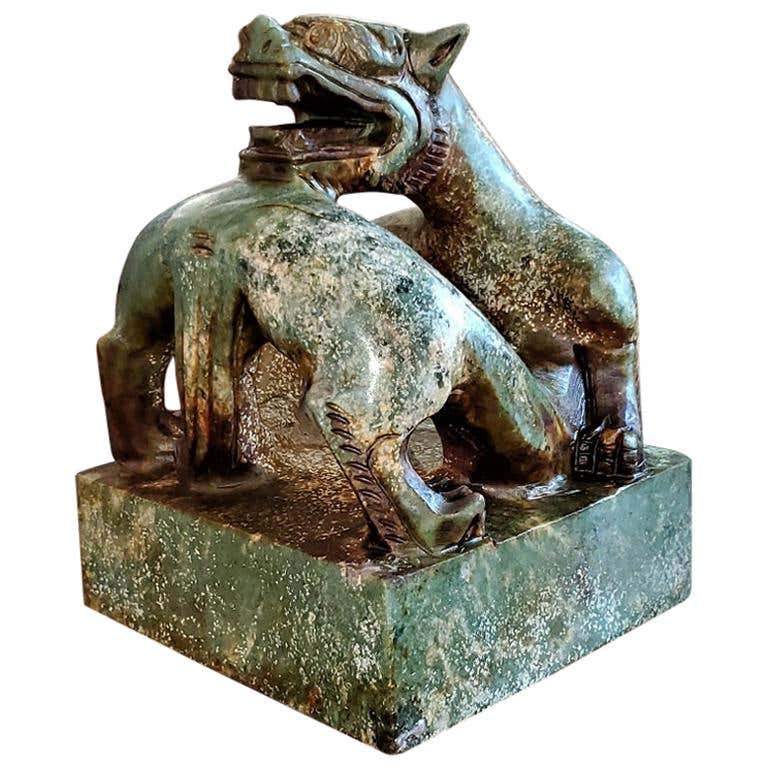

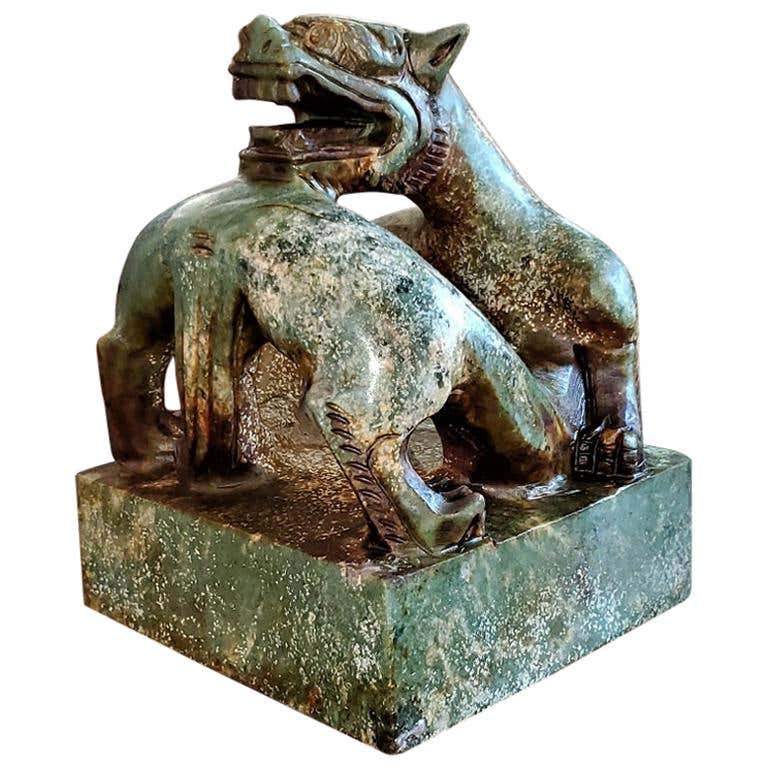

Vintage Chinese Green & Brown Jadeite Serpentine Foo Dog Chop Seal

PRESENTING A RARE Vintage Chinese Green & Brown Jadeite Serpentine Foo Dog Chop Seal.

Hong Kong/Chinese, circa 1950.

A fantastically carved Foo Dog in a contorted form, hand-carved from a single piece of mottled green, brown and white jadeite.

Initially, we thought this was made of marble, but then we realized that marble is a very porous rock and would absorb any ink that would be used for stamping the seal on the base. Clearly, marble would not be suitable for that purpose and when we compared the piece to ‘jadeite’ it was obvious that it was made of jadeite.

Seal on the base.

Really nice size.

Bought by a Dallas Private Collector in Hong Kong/China in the 1970’s.

A seal, in an East and Southeast Asian context, is a general name for printing stamps and impressions thereof which are used in lieu of signatures in personal documents, office paperwork, contracts, art, or any item requiring acknowledgement or authorship. In the western world they were traditionally known by traders as chop marks or simply chops. The process started in China and soon spread across East Asia. China, Japan and Korea currently use a mixture of seals and hand signatures, and, increasingly, electronic signatures.

Chinese seals are typically made of stone, sometimes of metals, wood, bamboo, plastic, or ivory, and are typically used with red ink or cinnabar paste (Chinese: 朱砂; pinyin: zhūshā). The word 印 (“yìn” in Mandarin, “in” in Japanese and Korean, pronounced the same) specifically refers to the imprint created by the seal, as well as appearing in combination with other ideographs in words related to any printing, as in the word “印刷”, “printing”, pronounced “yìnshuā” in Mandarin, “insatsu” in Japanese. The colloquial name chop, when referring to these kinds of seals, was adapted from the Hindi word chapa and from the Malay word cap, meaning stamp or rubber stamps. In Japan, seals (hanko) have historically been used to identify individuals involved in government and trading from ancient times. The Japanese emperors, shōguns, and samurai each had their own personal seal pressed onto edicts and other public documents to show authenticity and authority. Even today Japanese citizens’ companies regularly use name seals for the signing of a contract and other important paperwork

In Japan, seals in general are referred to as inkan (印鑑) or hanko (判子). Inkan is the most comprehensive term; hanko tends to refer to seals used in less important documents.

The first evidence of writing in Japan is a hanko dating from AD 57, made of solid gold given to the ruler of Nakoku by Emperor Guangwu of Han, called King of Na gold seal. At first, only the Emperor and his most trusted vassals held hanko, as they were a symbol of the Emperor’s authority. Noble people began using their own personal hanko after 750, and samurai began using them sometime during the Feudal Period. Samurai were permitted exclusive use of red ink. After modernization began in 1870, hanko came into general use throughout Japanese society.

Government offices and corporations usually have inkan specific to their bureau or company and follow the general rules outlined for jitsuin with the following exceptions. In size, they are comparatively large, measuring 2 to 4 inches (5.1 to 10.2 cm) across. Their handles are often extremely ornately carved with friezes of mythical beasts or hand-carved hakubun inscriptions that might be quotes from literature, names and dates, or original poetry. The Privy Seal of Japan is an example; weighing over 3.55 kg and measuring 9.09 cm in size, it is used for official purposes by the Emperor.

Some seals have been carved with square tunnels from handle to underside, so that a specific person can slide their own inkan into the hollow, thus signing a document with both their name and the business’s (or bureau’s) name. These seals are usually stored in jitsuin-style boxes under high security except at official ceremonies, at which they are displayed on extremely ornate stands or in their boxes.

For personal use, there are at least four kinds of seals. In order from most formal/official to least, they are jitsuin, ginkō-in, mitome-in, and gagō-in.

A jitsuin (実印) is an officially registered seal. A registered seal is needed to conduct business and other important or legally binding events. A jitsuin is used when purchasing a vehicle, marrying, purchasing land, and so on.

The size, shape, material, decoration, and lettering style of jitsuin are closely regulated by law. For example, in Hiroshima, a jitsuin is expected to be roughly 1⁄2 to 1 inch (1.3 to 2.5 cm), usually square or (rarely) rectangular but never round, irregular, or oval. It must contain the individual’s full family and given name, without abbreviation. The lettering must be red with a white background (shubun), with roughly equal width lines used throughout the name. The font must be one of several based on ancient historical lettering styles found in metal, woodcarving, and so on. Ancient forms of ideographs are commonplace. A red perimeter must entirely surround the name, and there should be no other decoration on the underside (working surface) of the seal. The top and sides (handle) of the seal may be decorated in any fashion from completely undecorated to historical animal motifs to dates, names, and inscriptions.

Throughout Japan, rules governing jitsuin design are so stringent and each design is unique so the vast majority of people entrust the creation of their jitsuin to a professional, paying upward of US$20 and more often closer to US$100, and using it for decades. People desirous of opening a new chapter in their lives—say, following a divorce, death of a spouse, a long streak of bad luck, or a change in career—will often have a new jitsuin made.

The material is usually a high quality hard stone or, far less frequently, deerhorn, soapstone, or jade. It is sometimes carved by machine. When it’s carved by hand, an intō (“seal-engraving blade”), a mirror, and a small specialized wooden vice are used. An intō is a flat-bladed pencil-sized chisel, usually round or octagonal in cross-section and sometimes wrapped in string to give the handle a non-slip surface. The intō is held vertically in one hand, with the point projecting from one’s fist on the side opposite one’s thumb. New, modern intō range in price from less than US$1 to US$100.

The jitsuin is kept in a very secure place such as a bank vault or hidden carefully in one’s home. They are usually stored in thumb-sized rectangular boxes made of cardboard covered with heavily embroidered green fabric outside and red silk or red velvet inside, held closed by a white plastic or deerhorn splinter tied to the lid and passed through a fabric loop attached to the lower half of the box. Because of the superficial resemblance to coffins, they are often called “coffins” in Japanese by enthusiasts and hanko boutiques. The paste is usually stored separately.

A ginkō-in (銀行印) is used specifically for banking; ginkō means “bank”. A person’s savings account passbook contains an original impression of the ginkō-in alongside a bank employee’s seal. Rules for the size and design vary somewhat from bank to bank; generally, they contain a Japanese person’s full name. A Westerner may be permitted to use a full family name with or without an abbreviated given name, such as “Smith”, “Bill Smith”, “W Smith” or “Wm Smith” in place of “William Smith”. The lettering can be red or white, in any font, and with artistic decoration.A foreigner’s ginkō-in displayed in a typical Japanese savings account passbook. Note the boundary showing maximum size (1.0 by 1.5 centimetres (0.39 in × 0.59 in)) and extreme design freedom in font and decoration.

Most people have them custom-made by professionals or make their own by hand, since mass-produced ginkō-in offer no security. They are wood or stone and carried about in a variety of thumb-shape and -size cases resembling cloth purses or plastic pencil cases. They are usually hidden carefully in the owner’s home.

Banks always provide stamp pads or ink paste, in addition to dry cleaning tissues. The banks also provide small plastic scrubbing surfaces similar to small patches of red artificial grass. These are attached to counters and used to scrub the accumulated ink paste from the working surface of customers’ seals.

A mitome-in (認印) is a moderately formal seal typically used for signing for postal deliveries, signing utility bill payments, signing internal company memos, confirming receipt of internal company mail, and other low-security everyday functions.

Mitome-in are commonly stored in low-security, high-utility places such as office desk drawers and in the anteroom (genkan) of a residence.

A mitome-in’s form is governed by far fewer customs than jitsuin and ginkō-in. However, mitome-in adhere to a handful of strongly observed customs. The size is the attribute most strongly governed by social custom. It is usually the size of an American penny or smaller. A male’s is usually slightly larger than a female’s, and a junior employee’s is always smaller than his bosses’ and his senior co-workers’, in keeping with office social hierarchy. The mitome-in always has the person’s family name and usually does not have the person’s given name (shita no namae). They are often round or oval, but square ones are not uncommon, and rectangular ones are not unheard-of. They are always geometric figures. They can have red lettering on a blank field (shubun) or the opposite (hakubun). Borderlines around their edges are optional.

Plastic mitome-in in popular Japanese names can be obtained from stationery stores for less than US$1, though ones made from inexpensive stone are also very popular. Inexpensive prefabricated seals are called sanmonban (三文判). Prefabricated rubber stamps are unacceptable for business purposes.

Mitome-in and lesser seals are usually stored in inexpensive plastic cases, sometimes with small supplies of red paste or a stamp pad included.

Most Japanese also have a far less formal seal used to sign personal letters or initial changes in documents; this is referred to by the broadly generic term hanko. They often display only a single hiragana, kanji ideograph, or katakana character carved in it. They are as often round or oval as they are square. They vary in size from 0.5-to-1.5-centimetre wide (0.20 to 0.59 in); women’s tend to be small.

Gagō-in (雅号印) are used by graphic artists to both decorate and sign their work. The practice goes back several hundred years. The signatures are frequently pen names or nicknames; the decorations are usually favorite slogans or other extremely short phrases. A gago in can be any size, design, or shape. Irregular naturally occurring outlines and handles, as though a river stone were cut in two, are commonplace. The material may be anything, though in modern times soft stone is the most common and metal is rare.A modern gagō-in spelling out “Mitsuko” (光子), a popular woman’s given name in Japan. Note the uniform line widths and extremely archaic forms of the ideographs for “fire/light/bright” (mitsu, 光) and “child” (ko, 子), read right-to-left.

Traditionally, inkan and hanko are engraved on the end of a finger-length stick of stone, wood, bone, or ivory, with a diameter between 25 and 75 millimetres (0.98 and 2.95 in). Their carving is a form of calligraphic art. Foreign names may be carved in rōmaji, katakana, hiragana, or kanji. Inkan for standard Japanese names may be purchased prefabricated.

Almost every stationery store, discount store, large book store, and department store carries small do-it-yourself kits for making hanko. These include instructions, hiragana fonts written forward and in mirror-writing (as they’d appear on the working surface of a seal), a slim in tou chisel, two or three grades of sandpaper, slim marker pen (to draw the design on the stone), and one to three mottled, inexpensive, soft square green finger-size stones.

In modern Japan, most people have several inkan.

A certificate of authenticity is required for any hanko used in a significant business transaction. Registration and certification of an inkan may be obtained in a local municipal office (e.g., city hall). There, a person receives a “certificate of seal impression” known as inkan tōroku shōmei-sho (印鑑登録証明書).

The increasing ease with which modern technology allows hanko fraud is beginning to cause some concern that the present system will not be able to survive.

Signatures are not used for most transactions, but in some cases, such as signing a cell phone contract, they may be used, sometimes in addition to a stamp from a mitome-in. For these transactions, a jitsuin is too official, while a mitome-in alone is insufficient, and thus signatures are used.

Link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seal_(East_Asia)#Japanese_usage

Jadeite is a hard, extremely tough, rare mineral of the clinopyroxene family of minerals. Though highly variable in color, it is typically apple-green to emerald-green, or less commonly white or white with spots of green.

Jadeite is the dominant mineral of the most desirable variety of jade. This was prized in traditional Chinese culture, where it was worked into a great variety of beautiful ornaments and utensils.

Jadeite was also used by Stone Age peoples for implements and weapons.

Jade received its name, “piedra de ijada” (“stone of the side”), because it was once thought to cure kidney ailments when applied to the side of the body.

Vintage Chinese Green & Brown Jadeite Serpentine Foo Dog Chop Seal

Provenance: From a Private Dallas Collection.

Condition: Very good. One chipped ear, otherwise very good.

Dimensions: 5 inches Tall, 4 inches Wide and 4 inches Deep

SALE PRICE NOW: $700