The Meaning of Being ‘Irish’ in Today’s World

‘THE MEANING OF BEING ‘IRISH’ IN TODAY’S WORLD.’

WHY WE ‘MUST’, LEARN FROM OUR PAST,

TO TRULY UNDERSTAND WHO WE ARE TODAY.

(The Personal Musings, of a 100% Native Irishman & Recent US Immigrant)

To ALL … I say …. ‘Céad Míle Fáilte”!

Many people, have recently expressed opinions on what is means to be ‘Irish’.

Some people back home in Ireland, have become quite ‘fixated’ on their notion of what constitutes ‘Irishness” and have indeed ‘insulted’ many of the Irish ‘diaspora’ in calling them somewhat ‘less than Irish’, ‘Plastic Paddies’ or ‘Irish Lite’, for want of better words or descriptions.

The ‘native Irish’ have developed an abhorrence, to what they perceive as ‘Paddywhackery’ or the hostile take-over, theft and replacement of ‘Irish identity’, with what they perceive as foreign inventions of “Irishness’. They especially ‘rail’ at the ‘leprechaun suits’, the ‘green beers’ and the various exhibitions of ‘Stereotypical Irishness’ around the World on St. Patrick’s Day. They cringe when they hear ‘St. Patty’s”.

It is these opinions and attitudes, that have ‘spurred me on’, to write my opinion on the topic. I have threatened to write this article for years and ‘now is the time’!

Let me start my response with some simple questions:

Being “Irish’, what does that REALLY mean?

Does it mean, being born in the “Emerald Isle’?

Does it mean, tracing your parents and/or grandparents to being born on the Island that is Ireland?

Does it mean, tracing your ancestors beyond your grandparental lineage?

Does it mean, wearing green and celebrating on St. Patrick’s Day?

Does it mean, just ‘feeling’ Irish?

These are some of the myriad of questions surrounding the definition of being ‘Irish’, and inevitably someone is going to be disappointed and disagree, with my personal answer(s).

In today’s Ireland, there is much division and debate on the definition of what constitutes being ‘Irish’.

On the one hand, you have some who feel, that one must be born in Ireland to be considered truly ‘Irish’. They refer to almost everyone else as ‘Plastic Paddies’. This is a very ‘nationalistic’ and/or ‘nativist’ opinion and it simply does not stand up to greater scrutiny, cross-examination or historical context.

Firstly, that opinion falls apart when you ask these people, if ‘naturalized’ Irish citizens are indeed “Irish’? These folk (naturalized citizens), have lived in Ireland for over 5 years and made a commitment to assimilate into Irish Society in every way. Indeed, they have sworn an oath of allegiance to the State when taking up citizenship, which is more than any native Irish born person has had to do.

Secondly, when you ask these people how they feel about many of our sporting heroes over the last 20/30 years, who were not born in Ireland, they often have a very different viewpoint. Take as an example, the famous Cork GAA Star brothers of Seán Óg Ó hAilpín and Setanta Ó hAilpín,. The elder was born in Fiji and the younger born in Australia OR the current ‘sprinting phenom’ of Rashidat Adeleke, a serious prospect for Olympic sprinting gold in future Olympics, born and raised in Dublin, with Nigerian parents who immigrated and became naturalized citizens.

Are the Ó hAilpín Brothers NOT Irish? Of course, they are and most native Irishmen would agree, including the ones complaining about ‘Plastic Paddies’ (especially the ones in red shirts).

Is Rashidat, any less Irish, because her parents were immigrants? Hell no.

After all, St. Patrick himself was not born in Ireland but ‘naturalized’ and became the most famous Irishman of all time!

To truly understand what being ‘Irish’ means, one has to simply look at our history –

From the beginning of recorded history, the ‘Irish’ have always been ‘travelers’ , ‘explorers’ and ‘migrants’.

Even prior to recorded history, there is fresh evidence of our travelling ‘bug’.

Recent discoveries of remains of ancient bodies found in Northern Ireland (Currie’s Pub, on Rathlin Island off the coast of Co Antrim), coupled with DNA testing and carbon dating, have changed for many, what was always the widely held opinion that the Irish are descended from Celts, who migrated to Ireland from Central Europe.

DNA researchers found that the three skeletons found under Currie’s pub, are the ancestors of modern Irish people and predate the Celts’ arrival on Irish shores by around 1,000 years.

Essentially, Irish DNA existed in Ireland, before the Celts ever set foot on the island.

Instead, Irish ancestors may have come to Ireland from the Bible lands in the Middle East. They might have arrived in Ireland from the South Meditteranean and would have brought cattle, cereal, and ceramics with them.

The Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (PNAS) said in 2015 that the bones strikingly resembled those of contemporary Irish, Scottish, and Welsh people.

A retired archaeology professor at the highly-renowned University of Oxford said that the discovery could completely change the perception of Irish ancestry.

“The DNA evidence based on those bones completely upends the traditional view,” said Barry Cunliffe, an emeritus professor of archaeology at Oxford.

Radiocarbon dating at Currie’s McCuaig’s Bar, found that the ancient bones date back to at least 2,000 BC, which is hundreds of years older than the oldest known Celtic artifacts anywhere in the world.

Dan Bradley, a genetics professor at Trinity College, said in 2016 that the discovery could challenge the popular belief that Irish people are related to Celts.

“The genomes of the contemporary people in Ireland are older — much older — than we previously thought,” he said.

Leading to the new opinion, by some experts, that the ‘Irish Celtic gene’ may have originally been, in fact, uniquely ‘Irish’ and that it was in fact, these Irish Celts, migrating from Ireland to Northern Spain and Central Europe, that caused the spread of the Celtic gene in those regions (rather than the other way around).

So, it appears that our Irish Celtic ancestors, were the original ‘travelers/explorers’.

In early history, the Irish were renowned for being raiders of mainland Britain. This was how St. Patrick was enslaved and brought to Ireland. They even raided Scotland and records show that the Picts were concerned over the take-over of parts of Scotland by the ‘Irish’. One could say that the Irish invented ‘raiding and pillaging’ long before the Vikings arrived on the scene.

It appears that this ‘raiding and pillaging’ lifestyle came to a fairly abrupt end, with the rise of St. Patrick and the Catholic Church in Ireland.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, whilst the Rest of Europe was suffering through ‘The Dark Ages’, our ancestors are regarded by many scholars, as having saved ‘civilization’.

Thomas Cahill’s superb book on ‘How the Irish Saved Civilization’ deals with this issue in greater depth.

St. Patrick, St. Columba and their monks, not only saved thousands of priceless manuscripts and books from loss, and utter destruction and oblivion, but they also sent many Irish ‘Missionaries’ around Europe, in an attempt to save civilization, teaching literacy, humanity and Christianity. These too, were ‘travelers’.

Legend has it in Ireland, that St. Brendan, may even have sailed to the New World, hundreds of years before the Vikings and Christopher Columbus.

In the various conflicts that arose over the Centuries many ‘Irish’ emigrated. Some to Scotland to fight with the Scots. Some to Spain, some to France. They traveled and fought for the Italians, the Swedes, The Austrians and The Poles. Remember the ‘Flight of the Earls and the Wild Geese’?

But the tale of modern day emigration from Ireland really starts in the 16th Century.

IRISH EMIGRATION TO THE NEW WORLD:

16th Century to 18th Century:

Irish American history really began in the late-16th century, with the transportation of petty criminals and beggars to the West Indies.

These “transportee’s”, were subsequently joined by prisoners of war, deported in the middle of the 17th Century, following Oliver Cromwell’s bloody conquest of Ireland, and forced to provide cheap (slave) labor to the Virginian and Caribbean tobacco plantations.

This issue has recently become a somewhat ‘hot’ and ‘highly contentious’ topic.

Were these Irish transportee’s, ‘slaves’ or ‘indentured servants’?

My position on this is quite clear. I am firmly of the belief that they were in fact ‘slaves’, by ANY definition of the term ‘slavery’.

I know that a lot of people and academics, will disagree with me on this (I have had many, many debates with historians and academics on this issue) and the ‘official’ teaching, appears to favor ‘indentured servitude’, but I fear that this has been driven by a ‘revisionist’ version of history (by mainly the British) in an attempt to (1) sanitize the enslavement of over 100,000 Irish political prisoners, (2) supported by some Irish academics, in order to be ‘politically correct’ and not wanting to offend our British cousins or diminish the suffering of our African American friends.

But the facts, simply do not support the notion that these people were ‘indentured’ servants.

As a former lawyer, I am fully educated in ‘Contract Law’. An essential ingredient of being an ‘indentured servant’ was that there was a written ‘Indenture’ (Contract/Deed) voluntarily entered into by both parties. It was a written contract setting out the terms of servitude, duration, compensation/consideration etc.

I have seen such ‘Indentures’ for later arrivals BUT NEVER an ‘Indenture’ that was signed by one of these transportee’s and I do not believe that any exist.

It is the first question I ask a ‘slavery’ denier and in EVERY single debate, not one single person can point to or produce as evidence to support their argument, the existence of such written Indentures for them. They make excuses such as “they were destroyed or lost”, “the servants would dispose of them so as to not be reminded or to move on in life”, “no records were ever kept”, etc. etc.

Absolute NONSENSE!

Firstly, the British were almost OCD, in keeping records,

Indentures could be registered with the Courts, so as to be enforced by a Court of Law if needed and it normally would be the beneficiary of the labor, who would do this to protect their investment.

Secondly, it was in the ‘indentured servants’ interests to retain a limited term written Indenture past the term of service, to prove that they had served their term of servitude, if ever questioned. This is the reason many of the later ‘Indentures’ still exist for examination.

If ANY such ‘Indenture’ existed for these early transportee’s, then then ‘slavery’ deniers would be producing them immediately! LOL.

On another legal note, even if such a Contract/Indenture was indeed signed, it would be ‘void’ under common law and equity, as it would clearly have been entered under the most extreme duress or coercion, namely, “Sign this Indenture of face death by execution”.

So, in the absence of any written Indenture, these people simply cannot be classified as ‘Indentured Servants”. These people were forcibly removed from their homeland, under threat of death, torn from their families, friends and neighbors, to work and labor on the plantations of their captors in the Caribbean and Virginia, for the gain of their captors and not as a free individuals making a voluntary decision to seek a better life.

The attempt by some to raise a distinction between Voluntary and Involuntary indentured servitude, is ridiculous ‘word play’ and an argument based in ‘semantics’, as under British Law, you could not enforce such a contract if it was entered into involuntarily.

I do accept however, that most of these transportee’s, ended up having better prospects than say, the African slaves, who were slaves in perpetuity, as were their offspring.

There is some compelling evidence, through early Colonial records and publications, that some of these ‘Irish Slaves’ were in fact sold as ‘chattel’ slaves in the 16th Century both in Virginian and Caribbean slave markets.

So comparing the two should, in no way diminish or detract from the absolutely abhorrent African slave trade, nor should they be placed or viewed in the same category. It is simply not a ‘competition”!

I am simply attempting to clarify Irish history, in an unvarnished manner.

In a nutshell, it is my firm belief, that these 16C Irish transportee’s were in fact, political prisoners, rebels, seditious persons, criminals and beggars, who facing certain death by the British and/or the cost of lifetime incarceration, were instead forcibly transported as ‘slaves for their lifetimes’, for the sole purpose of providing free labor to the loyalist Plantation owners in the New World.

I accept, however, that ‘many’, were only subjected to slave like conditions, for a limited number of years because either (1) the were granted their freedom (2) they escaped their confinement and became pirates/privateers or (3) they escaped to Louisiana Territory and the protection of the French.

Others, were not so lucky and served out the rest of their lives in slavery.

The island of Montserrat in the Caribbean is a classic example. The home of the original ‘Black Irish’. In the Mid-17th Century, the British version of that island’s history is that most of the settlers were Irish. They refer to most of them as ‘indentured servants’ but then describe how many of them were merchants or plantation owners themselves. This is directly in contradiction of the British ‘Penal Laws’ which existed at that time, which ‘banned’ Irish Catholics from voluntarily emigrating (this ban continuing until the late 1820’s), owning property etc etc.

So we can easily assume, that these ‘men of status’, were not Irish Catholics, but most likely either -(1) Scottish Planters (not just from Ulster as other parts of Ireland were also ‘planted’ during the 16th Century) or (2) English Landlords with Irish holdings or (3) Protestant Irish loyal to the Crown or (4) Irish loyalists who renounced their Catholicism, for personal advancement.

Again, this twisted and biased version of history is very ‘short on detail’ of the Irish that were brought to the Island from Virginia in the mid-17C.

They describe them as ‘settlers’ and ‘cultivators of their own little farms’. I have no doubt in my mind that these Virginia settlers were in fact, some of the original ‘Irish Slaves’ that were forcibly sent to Virginia and then a number of them ‘sold’ to the plantation owners in Montserrat.

These Irish Slaves were then supplemented by the arrival of African Slaves.

They lived in the same accommodation, they did the same work, their living conditions were identical. They interbred, intermarried, shared cultures, folklore and songs. This led to a very interesting combination of modern day natives of Montserrat speaking with a slight ‘Cork’ accent and singing Irish traditional songs … hence, the term “Black Irish’!

Again, the revisionist version of history that we read, states that most of the early Irish in the Caribbean were Catholics from the southern counties of Ireland. One of the largest such Irish communities was on the island of Barbados. Again, a ‘conundrum’ and ‘contradiction’ because of the Penal Laws.

I am not saying that all were slaves …. far from it …. indentured servitude existed and there are Deeds to prove it BUT no deeds exist for those ‘forcibly removed’ and the Irish Catholics who left voluntarily by way of Indentured Servitude prior to 1825 had to (1) renounce their faith and (2) pledge allegiance to the Crown. I’m certain many did this to try and obtain a better life, but probably with crossed fingers behind their backs! LOL

As African slavery expanded in the Caribbean, the descendants of the Irish deportees/slaves started to leave the islands and many looked to North America as the place to seek their fortune.

Many of these Barbados-born Irish were among the early settlers of Carolina.

Around this time (the 1700s), the stream of Irish immigrants to America had been steady, but small in number, and pretty exclusively Protestant on account of the Penal laws, preventing Catholics from freely emigrating to the colonies.

The Irish linen industry had brought a good few across the Atlantic. Ships went in one direction with the flax seeds that Ireland needed to produce the raw materials of the trade, and returned with emigrants’ keen to satisfy the labor shortage and collect the high wages they’d heard so much about. Many ‘bought’ their passage by signing up for a ‘lengthy contract of work’ or ‘indentured servitude’.

IRISH AMERICAN HISTORY: 1720-1790:

The first significant wave of Irish American immigration came in the 1720’s. This period saw the arrival of the ‘Scots-Irish’, a term used in North America (but not elsewhere) to denote those who came from Ireland but had Scottish Presbyterian roots, from the plantation of large parts of Ireland in the 16th Century.

Philadelphia, was the most popular destination port for Scots-Irish immigrants to America, mainly because the linen trade routes were already well established. They then moved into the Appalachian regions, the Ohio Valley, New England, The Carolinas and Georgia.

Unlike the 19th century chapter of Irish American history, when Catholic Irish immigrants turned their back on the land, most Scots-Irish immigrants continued their farming traditions.

Small numbers of Irish Catholics also arrived in this period. They sailed from the southern Irish ports of Cork and Kinsale and some settled communities in Virginia and Maryland. But most of these were either (1) indentured servants or (2) renounced their faith in order to bypass the Penal Laws.

The number of Irish immigrants rose and fell during these years. It was high in the late 1720’s and low in the 1730’s, before rising in the 1740’s and continuing to grow until the 1760’s when some 20,000 departed from Ulster ports alone.

From 1770 to 1774 the human traffic peaked with the arrival of some 30,000 mostly Scots-Irish immigrants in America.

By 1790, America had a white population of 3,100,000. Nearly half a million (447,000) are estimated to have been either Irish-born or of Irish ancestry. Of these, some two-thirds (about 300,000) are thought to have originated in the province of Ulster.

In an interesting aside – These Scots-Irish immigrants did not call themselves ‘Scots-Irish or Ulster-Scots” until the mid 19th Century, when the massive influx of Irish Catholic immigrants (as a result of the Great Famine) led then to feel the need to be separately identified. Prior to that they were happy to be identified as ‘Irish’. This is why so many famous figures in America during that period, with that heritage, proudly called themselves simply ‘Irish’ … ‘Boone, Crockett, Bowie, Travis, Houston’ …. just to name a few famous to Texas. I think this ‘partially’ explains the American phenomenon of confusing Ireland and Scotland as somehow the same countries to this day! LOL

Irish American history: post American Independence:

After Independence, Irish American history stepped up a pace with an estimated one million Irish immigrants arriving between 1783 and 1844. The majority, at least until the 1820’s (with the ending of the Penal Laws), were artisans or professionals so they quickly assimilated and prospered.

The letters they sent home told of comforts the average Irish family could only dream of. Soon, many among the poorest were saving for their fare. This wave of Irish American immigration saw the unskilled and illiterate arrive, ready to seek their fortunes, and many found employment as laborers on some of America’s huge early infrastructure projects such as the Erie Canal.

While the pace of Irish American history cranked up a gear in the early 19th-century, it was nothing compared to the dramatic exodus caused by ‘The Great Hunger’ (also known as the ‘Irish Famine’ or the ‘Great Irish Genocide’ as some would now call it) of the late 1840’s.

Irish immigration to America after 1846 was predominantly Catholic. The vast majority of those that had arrived previously had been Protestants or Presbyterians and had quickly assimilated, not least because English was their first language, and most (but certainly not all) had skills and perhaps some small savings on which to start to build a new life. Very soon they had become independent and prosperous.

Irish immigration to America: The Famine Years:

The Great Famine (Irish: an Gorta Mór, or the Great Hunger was a period of mass starvation, disease, and emigration in Ireland between 1845 and 1852. It is sometimes referred to, mostly outside Ireland, as the Irish Potato Famine, because about two-fifths of the population was solely reliant on this cheap crop for a number of historical reasons.

During the famine, according to the “experts”, approximately one million people died and a million more emigrated from Ireland, causing the island’s population to fall by between 20% and 25%.

I absolutely disagree with these widely accepted academic figures. Again, it is an example of ‘revisionist’ history. The numbers don’t lie!

In the Census of Ireland in 1840, the island of Ireland had a population of 8.5 Million. In the 20 years time, the census of 1860, reveals a population of 4 Million. That is a loss of 4.5 Millions souls.

I accept, that in the region of 1 to 1.5 Million perished from starvation and disease, but where I disagree with the academics is the 1 Million emigration figure.

In my opinion, this is more likely as high as 3 Million souls, who were forced to emigrate to the 4 corners of the World, to avoid starvation.

Where did they all go ?

How is it not accurately recorded where they went to ?

I think some of the answers lie in my opinions on the origin of the Irish who emigrated to the Southern States referred to later.

The proximate cause of famine was potato blight, which ravaged potato crops throughout Europe during the 1840’s. However, the impact in Ireland was disproportionate, as one third of the population was dependent on the potato for a range of ethnic, religious, political, social, and economic reasons, such as land acquisition, absentee landlords, and the Corn Laws, which all contributed to the disaster to varying degrees and remain the subject of intense historical debate.

The famine was a watershed in the history of Ireland, which was then part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The famine and its effects permanently changed the island’s demographic, political, and cultural landscape. For both the native Irish and those in the resulting diaspora, the famine entered folk memory and became a rallying point for first nationalist movements. The already strained relations between many Irish and the British Crown soured further, heightening ethnic and sectarian tensions, and boosting Irish nationalism and republicanism in Ireland and among Irish emigrants in the United States and elsewhere.

The arrival of destitute and desperate Catholics, many of whom spoke only Irish or a smattering of English, played out very differently. Suspicious of the majority Anglo-American-Protestants (a historically-based trait that was reciprocated), and limited by a language barrier, illiteracy and lack of skills, this wave of Irish immigrants sought refuge among their own kind.

They set up sizeable ethnic ghettos in cities along the north-eastern seaboard.

At this time, when famine was raging in Ireland, Irish immigration to America came mainly from two directions: by transatlantic voyage to the East Coast Ports (primarily Boston and New York) or by land or sea from Canada, then called British North America. Strong evidence has also emerged of transatlantic voyages to Southern US Ports which I will delve into later.

Ireland was also part of Britain, and fares to Canada were cheaper than fares to the USA, especially after 1847. Huge numbers of starving and sick Irish tried to escape certain death in Ireland by setting sail for Canada, enduring appalling conditions on vessels that have become known as coffin ships.

Those that survived the journey often had just one thought on their minds: to be free of British oppression. While many chose to settle in Canada, substantially more managed to find the physical and financial resources to reach America.

To this day, Newfoundland has a strong Irish presence. The people in St. John’s even speak with a type of Dublin accent. If you have ever watched the Canadian T.V. show ‘The Republic of Doyle” you will know what I mean.

Many people do not realize that there was a second Famine in Ireland in 1879. The Irish famine of 1879 was the last main Irish Famine. Unlike the earlier Great Famines of 1740 – 1741 and 1845 – 1852, the 1879 famine (sometimes called the “mini-famine” or an Gorta Beag) caused hunger rather than mass deaths, due to changes in the technology of food production, different structures of land-holding (the disappearance of the sub-division of land and of the cottier class as a result of the earlier Great Famine), income from Irish emigrants abroad which was sent to relatives back in Ireland, and in particular a prompt response of the British government, which contrasted with its laisses-fair response in 1845–1852.

IRISH AMERICAN HISTORY – THE SOUTH:

This is a subject very dear to my heart and rarely discussed or mentioned in the history books.

When talking about Irish emigration to the US, we always hear about Boston, New York, Chicago and Ellis Island, BUT rarely do you hear about the Irish that emigrated to the Southern US, some by design, but many as a result of ‘duplicity’.

Prior to the American Civil War and after it, cotton was the largest commodity exported from the Southern US States. This cotton would be grown on Plantations, tended and harvested by African American slaves and brought to Port for shipping back to Britain (the main marketplace).

Ports like Charleston and New Orleans were the main cotton ports of the day.

The ships would sail from these Southern ports, fully laden with cotton, but once the cargo had been unloaded in British Ports like, Bristol, Southampton, London and Liverpool the ship still needed to make the return journey to their port of origin.

The best form of ‘ballast’ for an empty cotton ship was ‘human passengers’.

These ships would sell the cheapest fares to the New World, perfect for the really poor ‘Irish’. They would stop off in Cork, Kinsale or Clifden in Galway and collect their passengers. Conditions were horrific. Many of the Irish passengers were native Gaelic speakers. They wanted to get to New York or Boston, as they probably had relatives or friends who had already emigrated there. They were told that the ship was heading for Boston or New York, but it would in fact land in Virginia, South Carolina, Galveston or New Orleans.

Just imagine the surprise and absolute ‘terror’, that of one of these emigrants must have endured, surviving a horrendously perilous crossing only to land in ‘the likes of’ New Orleans, with French speaking natives, mosquitoes, alligators, snakes and humidity. They would also have experienced their first encounter with black people, let alone, black slaves. It must have been akin to landing on Mars for these poor, uneducated folk.

The folk ballad ‘The Lakes of Pontchartrain’ is worth listening to. (I personally like “The Coronas’ version). It’s writer is unknown, but we know that it became popular with Confederate soldiers returning from the Civil War. The first time I heard it, I immediately knew that it’s lyrics had been ‘penned’ by an Irish immigrant. It tells the story of one such Irish immigrant’s attempt to travel north from New Orleans and his predicament of having no money, no transport and his fear of his new surroundings. Only to be ‘saved’ by a beautiful and caring, ‘Creole’ girl.

But one thing is for certain about the Irish and that is their remarkable ability to make the best of a bad situation. Eternal optimism, coupled with healthy skepticism, an adventurous spirit, the ability to see humor in everything and a ‘get on with it’ attitude, are uniquely Irish traits.

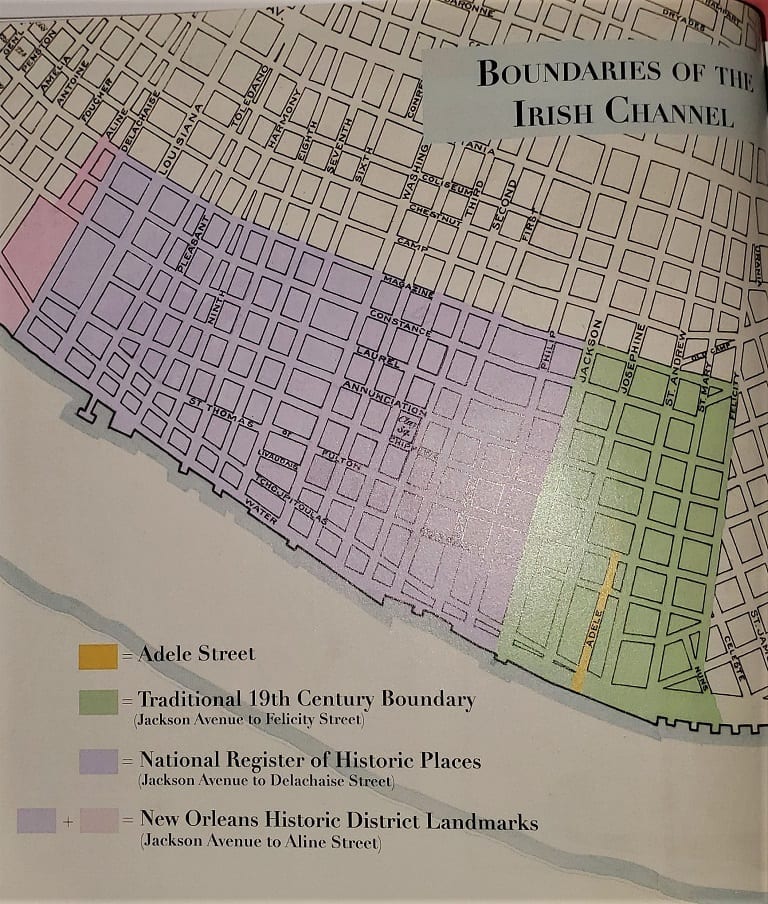

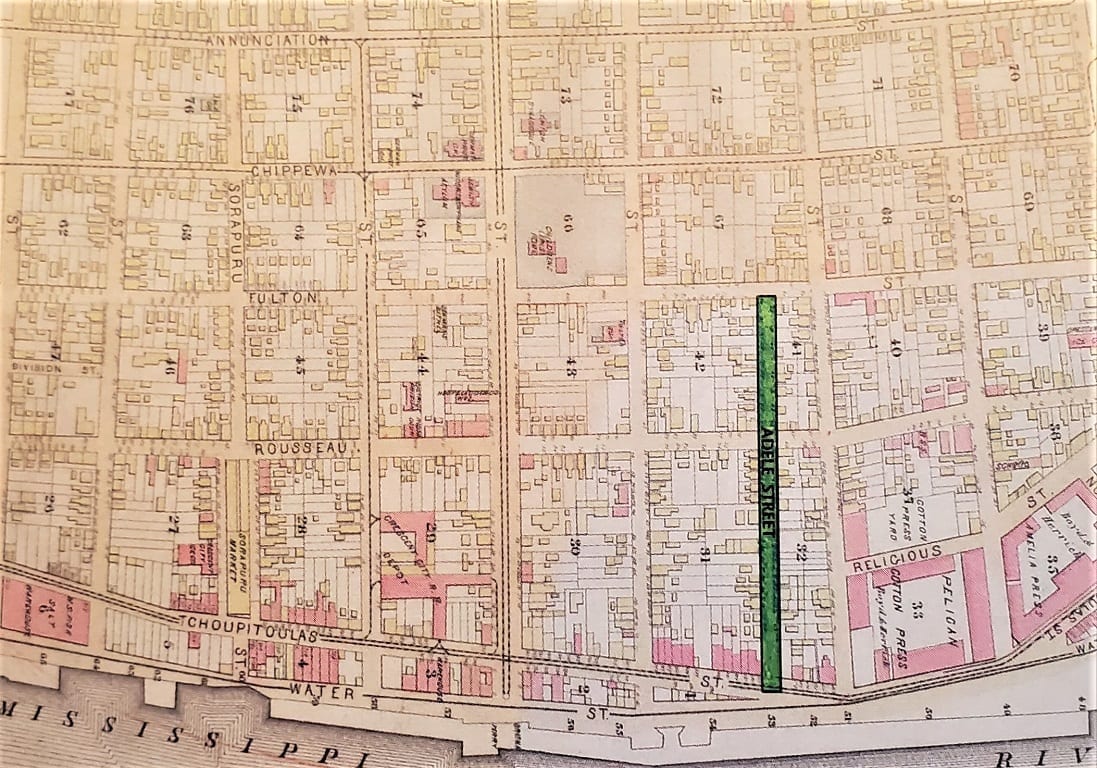

Many stayed in the South. In fact, there was an area of New Orleans known as ‘the Irish Channel’, where they settled in large numbers. By the 1830’s, New Orleans was already the second largest port in the country. And the Irish accounted for half of all the immigrants pouring into the city. But this was just the beginning. During the worst years of the Great Famine– between 1845 and 1860, at least two million Irish immigrants arrived in the U.S., at least 415,000 of whom ended up in New Orleans. By 1860, one of every five New Orleanians was Irish.

Many more decided to travel and expand further north and west.

Many settled in the Southern States of Louisiana, Georgia, Arkansas, The Carolinas, Kentucky, Tennessee and Virginia.

The City of Savannah, Georgia has one of the biggest St. Patrick’s Day parades in the US.

Many became involved in the Plantations, some as Foremen and some ultimately became owners.

Many of the African Americans, with Irish surnames, who are now often referred to erroneously as “Black Irish’, can trace their ancestry/name origin, to Irish slave owners (not one of our proudest moments, but part of our and our combined history nonetheless).

THE IRISH IN TEXAS:

Here in Texas, some of the first white settlers were Irish or Scots-Irish. There is even an exhibit in the Fort Worth Stockyard Museum commemorating these early Irish settlers.

A visit to the Alamo in San Antonio is truly ‘eye-opening’ for an Irish person.

We have all grown-up watching the movies about the Alamo with John Wayne and more recently Billy Bob Thornton, but what most people do not realize is that many ‘Irish’ died defending the Alamo from Santa Anna’s onslaught and also in the Texas War of Independence. Not only did, Travis, Bowie and Crockett all claimed Irish heritage (as did Sam Houston) but if one looks at the various plaques on the Alamo’s Walls commemorating their fallen heroes you will see the names, clearly Irish names, some have their County of origin noted as being from Co Cavan, Co Kerry etc. But many more with their place of origin being stated as from Tennessee, Arkansas, Kentucky, Virginia or New York, etc, but undeniably Irish surnames and probably only one or two generations removed from the ‘Old Country’. In all, a large percentage of those that died in the Alamo were “Irish”.

When I first visited the Alamo in 1999 I was shocked and amazed to discover this connection. I was more than ‘slightly peeved’ that they were not commemorating their Irish heroes at that time with an Irish Tri-color (as all other nationalities were represented by their national flag) and made my feelings known in no uncertain terms, to one of ‘The Daughters of the Republic’, who operate the Alamo. After much debate about political correctness and sensitivity over the ‘Troubles’ back home, they agreed to fly the Irish Tri-color, which still flies there today!

Irish immigration to America – Discrimination:

Notwithstanding the lack of trust between the predominantly Protestant America-born middle class and the impoverished Catholic immigrants who arrived in the mid-19th century, the main problem for the Irish immigrant was a lack of skill.

Of course, there were some who were blacksmiths, stonemasons, bootmakers and the like, but the majority had had no former formal training at anything.

On passenger manifests the men claimed to be laborers; women said they were domestic servants. In most cases, they had little or no previous experience in these roles; these positions were the limit of their aspirations.

A job – a wage – was what they were seeking, and they didn’t really care too much about the detail. Being unskilled, uneducated and typically illiterate, they accepted the most menial jobs that other immigrant groups did not want. So-called ‘Elegant Society’ looked down on them, and so did nearly everyone else!

They were forced to work long hours for minimal pay. Their cheap labor was needed by America’s expanding cities for the construction of canals, roads, bridges, railroads and other infrastructure projects, and also found employment in the mining and quarrying industries.

When the economy was strong, Irish immigrants to America were welcomed. But when boom times turned down, as they did in the mid-1850’s, social unrest followed and it could be especially difficult for immigrants who were considered to be taking jobs from Americans. Being already low in the pecking order, the Irish suffered great discrimination. ‘No Irish Need Apply’ was a familiar comment in job advertisements.

Irish immigration to America: Steamship competition:

After 1855, the tide of Irish immigration to America levelled off. However, the continuing steady numbers encouraged ship builders to construct bigger vessels. Most of them still made the voyage east with commodities to feed England’s industrial revolution, but ship owners began to realize the economic advantages of specializing in steerage passengers.

Conditions onboard began to improve. Not to a standard that could even remotely be called comfortable today. But improved, all the same.

By 1855 iron steamships of over 1500 tons were becoming increasingly common and competition was growing. So much so that steerage fares on steamships were often lower than on sailing ships, and voyage time was considerably quicker at less than two weeks.

This reduction of voyage time was a two-fold blessing. Not only did this mean the emigrant had to suffer the discomfort of steerage for a shorter period, it also made the concept of Irish immigration to America, the leaving of family and homeland seem less permanent.

As the size of emigrant ships grew, so it became increasingly common for Irish emigrants to travel to Liverpool, across the Irish Sea in Northwest England, to catch their boat to a new life in America. This huge port could accommodate the larger ships more easily than the small Irish harbors.

Immigration in New York: Castle Garden:

Where did these Irish immigrants to America settle?

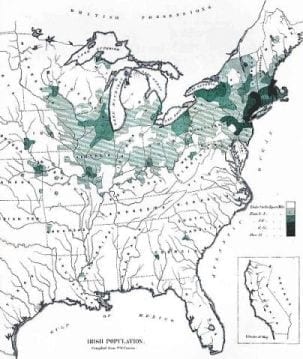

The map above shows the Irish population of the United States based on statistics from the 1890 census.

You will note with interest, the lack of color or ANY density of Irish populations reflected in the Southern States. In particular, the large numbers that lived in New Orleans (referred to earlier) do not even make a ‘blip’ on the Map.

The data reveals that immigration to New York had been the preference for nearly half a million (483,000) Irish-born settlers. Of these, 190,000 were in New York City.

More than a quarter of a million (260,000) had settled in Massachusetts, chiefly in Boston, while Illinois also had a sizeable population of 124,000 of which 79,000 were in Chicago.

New York was the principal entry point to the United States throughout the 19th century and on 3rd August 1855, a Board of Commissioners of Immigration opened the city’s first immigrant reception station.

Based at Castle Garden, near the Battery at the southern end of Manhattan, it had earlier been a fort, a cultural center and a theatre. Now it was pressed into service as a place to receive immigrants.

More than 8 million immigrants of all nationalities passed through Castle Garden before it closed on April 18, 1890. It is now a museum, and also the ticket office for the ferry to the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island.

Surviving Castle Gardens’ records are available on a free online database that also includes a sizeable collection of records dating from 1830 for other ports in America.

The records are mixed together, however, so if you find an entry for one of your ancestors, you will need to verify the port of entry. This can be done either through searching a microfilm of the ship’s manifest at NARA or through Ancestry’s online collection (fee charged). See below for links for more information.

Irish immigration to America: the turn of the Century:

After Castle Garden closed in 1890, Irish immigrants to America (and all other immigrants) were processed through a temporary Barge Office. Then, on 1st January 1892, the Ellis Island reception center opened. Annie Moore, a 15-year-old from Co Cork, was the first passenger processed, and more than 12 million followed her over the next 62 years.

By this time, attitudes towards the Irish had begun to change. The Civil War was probably the turning point; so many thousands of Irish whole-heartedly participated in the war (they made up the majority of no less than 40 Union regiments), and gained a certain respect and acceptance from Americans as a result. And second or third generation Irish-Americans had moved up the social and managerial ladder from their early laboring work. Some were even entering the professions.

Of course, this was not the lot of the majority. In the 1900 census there were still hundreds of thousands of Irish immigrants living in poverty, mostly in urban slums. But economic circumstances were improving for a significant proportion, and the Irish, as a group, were gaining footholds in the workplace, especially in the labor or trade union movement, the police and the fire service.

Their numbers helped. The large Irish populations of cities such as Boston, Chicago and New York were able to get their candidates elected to power, so launching the Irish American political class.

At the turn of the century, Irish born immigrants made up 2.12% of the US population. More importantly, Irish Americans, those Americans born to Irish parents made up 6.53%. A sizeable group, indeed.

See more at: http://www.irish-genealogy-toolkit.com/Irish-immigration-to-America.html#sthash.XSHqOykG.dpuf

Irish Immigration to America: 20th Century:

Irish emigration to the US continued with a relatively steady flow into the 20th Century. Whilst nowhere near the numbers that emigrated in the 19th Century, after the Great Famine, it was still an integral part of Irish life.

The Irish tradition of small farms, with the eldest son inheriting the farm, meant that large Catholic families faced a ‘quandary’. In the early to mid-20th Century, the options for the 2nd and later sons and daughters of poor rural families, were, in no particular order, join the priesthood or nuns, if female get married, be lucky to get a job in the Civil Service or become teachers or emigrate.

Many chose the latter.

At various stages through the 20th Century and depending on the State of the Irish Economy this lead to new and fresh waves of emigration. The 1950’s, the 1970’s, the 1980’s and more recently post the recession of 2008.

Anyone who lived in Ireland during the 20th Century will recall many rural areas decimated by emigration. One local GAA team in County Mayo could no longer even field a team due to the fact that most of the young people had left.

As an example of recent Irish-US Emigration, I spent the Summer of 1984 with my relatives in the Bronx, N.Y. on a J1 Student Visa. At that time, the Irish that had emigrated in the 1950’s had (like previous immigrants) ‘banded’ together in the area of the Bronx around Jerome Ave. Their children were all US born and raised, by the 1980’s. At that time, they were all concerned about the wave of immigrants arriving from Puerto Rico and settling in the Jerome Ave. area of the Bronx, resulting in the Irish neighborhoods being slowly pushed northwards. Due to the economic recession in Ireland in the 1980’s a new wave of Irish born immigrants arrived in New York and by the end of the 80’s and beginning of the 90’s they had in fact pushed the Puerto Rican immigrants back further South, thereby reclaiming the old neighborhoods. But this also led to a further problem (and an often repeated problem with immigration) in that, the Irish-Americans living in that neighborhood felt threatened by this new wave of native Irish, taking their jobs etc, which lead to violence and mini riots between the first generation Irish Americans and the new arrivals.

More recent emigration from Ireland post the turn of the 21st Century has been predominantly to Australia and to a lesser extent Canada, Dubai and the UAE.

THE IRISH IN AUSTRALIA:

Around 40,000 Irish convicts were transported to Australia between 1791 and 1867, including some who had participated in the Irish Rebellion of 1798, the 1803 Rising of Robert Emmet and the Young Ireland skirmishes in 1848.

Once in Australia, some were involved in the 1804 Castle Hill convict rebellion. Continual tension on Norfolk Island in the same year also led to an Irish revolt. Both risings were soon crushed. As late as the 1860s Fenian prisoners were being transported, particularly to Western Australia, where the Catalpa rescue of Irish radicals off Rockingham was a memorable episode.

Other than convicts, most of the laborers who voluntarily emigrated to Australia in the 19th century were drawn from the poorest sector of British and Irish society. After 1831, the Australian colonies employed a system of government assistance in which all or most immigration costs were paid for chosen immigrants, and the colonial authorities used these schemes to exercise some control over immigration. While these assisted schemes were biased against the poorest elements of society, the very poor could overcome these hurdles in several ways, such as relying on local assistance or help from relatives.

Most Irish emigrants to Australia were free settlers. The 1891 census of Australia counted 228,000 Irish-born. At the time the Irish made up about 27 percent of the immigrants from the British Isles. The number of Ireland-born in Australia peaked in 1891. A decade later the number of Ireland-born had dropped to 184,035. Dominion status for the Irish Free State in 1922 did not diminish arrivals from Ireland as Irish people were still British subjects. This changed after the Second World War, as people migrating from the new Republic of Ireland (which came into being in April 1949) were no longer British subjects eligible for the assisted passage. People from Northern Ireland continued to be eligible for this and continued to be seen officially as British. Only during the 1960s did migration from the south of Ireland reduce significantly. By 2002, around one thousand persons born in Ireland — north and south — were migrating permanently to Australia each year. For the year 2005-2006, 12,554 Irish entered Australia to work under the Working Holiday visa scheme.

Link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irish_Australians

Since the economic recession of 2008 (which destroyed the then vibrant Irish Economy called the ‘Celtic Tiger’), tens of thousands of “Irish” have either emigrated or travelled to Australia on Temporary or Permanent Work Visas.

Likewise, thousands have emigrated to Canada since 2008.

THE IRISH IN CANADA:

Irish Canadians (Irish: Gaedheal-Cheanadaigh) are Canadian citizens who have full or partial Irish heritage including descendants who trace their ancestry to immigrants who originated in Ireland. 1.2 million Irish immigrants arrived from 1825 to 1970, and at least half of those in the period from 1831–1850. By 1867, they were the second largest ethnic group (after the French), and comprised 24% of Canada’s population. The 1931 national census counted 1,230,000 Canadians of Irish descent, half of whom lived in Ontario. About one-third were Catholic in 1931 and two-thirds Protestant.

The Irish immigrants were overwhelmingly Protestant before the famine years of the late 1840s, when the Catholics started to come. Even larger numbers of Catholics headed to the United States; others went to England and Australia.

The 2006 census by Statistics, Canada, Canada’s Official Statistical office, revealed that the Irish were the 4th largest ethnic group, with 4,354,000 Canadians with full or partial Irish descent or 15% of the country’s total population. This was a large and significant increase of 531,495 since the 2001 census, which counted 3,823,000 respondents quoting Irish ethnicity. According to the National Household Survey 2011, the population of Irish ancestry has increased since 2006 to 4,544,870.

The first recorded Irish presence in the area of present-day Canada dates from 1536, when Irish fishermen from Cork traveled to Newfoundland.

After the permanent settlement in Newfoundland by Irish in the late 18th and early 19th century, overwhelmingly from Waterford, increased immigration of the Irish elsewhere in Canada began in the decades following the War of 1812. Between 1825 and 1845, 60% of all immigrants to Canada were Irish; in 1831 alone, some 34,000 arrived in Montreal.

The peak period of entry of the Irish to Canada in terms of sheer numbers occurred between 1830 and 1850, when 624,000 arrived; in contextual terms, at the end of this period, the population of the provinces of Canada was less 2 million. During this period much smaller numbers arrived in Newfoundland. Besides Upper Canada (Ontario), Lower Canada Quebec, the Maritime colonies of Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick, especially Saint John, were arrival points. Not all remained, many out-migrated to the United States or to Western Canada in the decades that followed. Seldom few ever returned to Ireland.

During the Great Famine, Canada received the most destitute Irish Catholics, who left Ireland in grave circumstances. Land estate owners in Ireland would either evict landholder tenants to board on returning empty lumber ships, or in some cases pay their fares. Others left on ships from the overcrowded docks in Liverpool and Cork.

Most of the Irish immigrants who came to Canada and the United States in the nineteenth century and before were Irish speakers, with many knowing no other language on arrival.

The great majority of Irish Catholics arrived in Grosse Isle, an island in Quebec in theSt Lawrence River, which housed the immigration reception station. Thousands died or arrived sick and were treated in the hospital (equipped for less than one hundred patients) in the summer of 1847; in fact, many ships that reached Grosse-Île had lost the bulk of their passengers and crew, and many more died in quarantine on or near the island. From Grosse-Ile, most survivors were sent to Quebec City and Montreal, where the existing Irish community mushroomed. The orphaned children were adopted into Quebec families and accordingly became Quebecois, both linguistically and culturally. At the same time, ships with the starving also docked at Partridge Island, New Brunswick in similarly desperate circumstances.

A large number of the families that survived continued on to settle in Canada West (now Ontario) and provided a cheap labor pool and colonization of land in a rapidly expanding economy in the decades after their arrival.

In comparison with the Irish who went to the United States or Britain, many Irish arrivals in Canada settled in rural areas, in addition to the cities.

The Catholic Irish and Protestant (Orange) Irish were often in conflict from the 1840s. In Ontario, the Irish fought with the French for control of the Catholic Church, with the Irish generally successful. In that instance, the Irish sided with the Protestants to oppose (unsuccessfully) the demand for French language Catholic schools.

Thomas Darcy McGee, an Irish-Montreal journalist, became a Father of Confederation in 1867. An Irish Republican in his early years, he would moderate his view in later years and become a passionate advocate of Confederation. He was instrumental in enshrining educational rights for Catholics as a minority group in the Canadian Constitution. In 1868, he was assassinated in Ottawa. Historians are not sure who the murderer was, or what were his motivations. One theory is that a Fenian, Gaylord O’Neil Whelan, was the assassin, attacking McGee for his recent anti-Raid statements. Others argue that Whelan was used as a scapegoat.

After Confederation, Irish Catholics faced more hostility, especially from Protestant Irish in Ontario, which was under the political sway of the already entrenched anti-Catholic Orange Order. The anthem “The Maple Leaf Forever,” written and composed by Scottish immigrant and Orangeman Alexander Muir, reflects the pro-British Ulster loyalism outlook typical of the time with its disdainful view of Irish Republicanism. As the Irish became more prosperous and newer groups arrived on Canada’s shores, tensions subsided through the remainder of the 19th century.

Link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irish_Canadians

THE IRISH IN GREAT BRITAIN:

Irish migration to Great Britain has occurred from the earliest recorded history to the present. There has been a continuous movement of people between the islands of Ireland and Great Britain due to their proximity. This tide has ebbed and flowed in response to politics, economics and social conditions of both places. Ireland was a feudal Lordship of the Kings of England between 1171 and 1541; a Kingdom in personal union with the Kingdom of England and Kingdom of Great Britain between 1542 and 1801; and politically united with Great Britain as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland between 1801 and 1922. Today, Ireland is divided between the independent Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

Today, millions of residents of Great Britain are either from Ireland or have Irish ancestry. It is estimated that as many as six million people living in the UK have at least one Irish grandparent (around 10% of the UK population).

The Irish diaspora (Irish: Diaspóra na nGael) refers to Irish people and their descendants who live outside Ireland. This article refers to those who reside in Great Britain, the largest island and principal territory of the United Kingdom

During the Dark Ages, significant Irish settlement of western Britain took place. The ‘traditional’ view is that Gaelic Language and culture was brought to Scotland, probably in the 4th century, by settlers from Ireland, who founded the Gaelic kingdom of Dal Riata on Scotland’s west coast. This is based mostly on medieval writings from the 9th and 10th centuries. However, recently some archeologists have argued against this view, saying that there is no archeological or place name evidence for a migration or a takeover by a small group of elites. Due to the growth of Dál Riata, in both size and influence, Scotland became almost wholly Gaelic-speaking until Northumbrian English began to replace Gaelic in the Lowlands, Gaelic remained the dominant languages of the Highlands into the 19th century, but has since declined.

Before and during the Gregorian Mission of 596 AD, Irish Christians such as Columba (521–97), Buriana, Diuma, Ceollach, Saint Machar, Saint Cathan, Saint Blane, Jaruman, Wyllow, Kessog, St Govan, Donnan of Eig, Foillan and Saint Fursey began the conversion of the British, Picts and early English peoples. Modwenna and others were significant in the following century.

Some English monarchs, such as Oswiu of Northumbria (c. 612 – 15 February 670), Aldfrith (died 704 or 705) and Harold Godwinson (died 1066) were either raised in or sought refuge in Ireland, as did Welsh rulers such as Gruffudd ap Cynan. Alfred the Great may have spent some of his childhood in Ireland.

In the year 902 Vikings who had been forced out of Ireland were given permission by the English to settle in Wirral, in the north west of England. An Irish historical record known as “The Three Fragments” refers to a distinct group of settlers living among these Vikings as “Irishmen”. Further evidence of this Irish migration to Wirral comes from the name of the village of Irby in Wirral, which means “settlement of the Irish”, and St Bridget’s church, which is known to have been founded by “Vikings from Ireland”.

Irish people who made Britain their home in the later medieval era included Aoife MacMurrough, Princess of Leinster (1145–88), the poet Muireadach Albanach (fl. 1213), the lawyer William of Drogheda (died 1245), Maol Mhuire O’Lachtain (died 1249), Malachias Hibernicus (fl. 1279–1300), Gilbert O Tigernigh (died 1323), Diarmait MacCairbre (executed 1490) and Germyn Lynch (fl. 1441–1483), all of whom made successful lives in Britain.

Historically, Irish immigrants to the United Kingdom in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were considered over-represented amongst those appearing in court. However, research suggests that policing strategy may have put immigrants at a disadvantage by targeting only the most public forms of crime, while locals were more likely able to engage in the types of crimes that could be conducted behind locked doors. An analysis of historical courtroom records suggests that despite higher rates of arrest, immigrants were not systematically disadvantaged by the British court system in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The most significant exodus followed the worst of a series of potato crop failures in the 1840s – the Great Famine. It is estimated that more than one million people died, and almost the same again emigrated. A further wave of emigration to England also took place between the 1930s, and 1960s by Irish escaping poor economic conditions following the establishment of the Irish Free State. This was furthered by the severe labor shortage in Britain during the mid-20th century, which depended largely on Irish immigrants to work in the areas of construction and domestic labor. The extent of the Irish contribution to Britain’s construction industry in the 20th century may be gauged from Sir William MacAlpine’s 1998 assertion that the contribution of the Irish to the success of his industry had been ‘immeasurable’.

Ireland’s population fell from more than 8 million to just 6.5 million between 1841 and 1851. A century later it had dropped to 4.3 million. By the late 19th century, emigration was heaviest from Ireland’s most rural southern and western Counties of Cork, Kerry, Galway, Mayo, Sligo, Tipperary and Limerick alone provided nearly half of Ireland’s emigrants. Some of this movement was temporary, made up of seasonal harvest laborers working in Britain and returning home for winter and spring. By the mid-1930s, Great Britain was the choice of many who had to leave Ireland. Britain’s wartime economy (1939–45) and post-war boom attracted many Irish people to expanding cities and towns such as London, Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham, Glasgow and Luton. Prior to the 2000’s financial crisis, ongoing sectarian violence and its economic aftermath was another major factor for immigration.

According to the UK 2001 Census, white Irish-born residents make up 1.2% of those living in England and Wales. In 1997, the Irish Government in its White Paper on Foreign Policy claimed that there were around two million Irish citizens living in Britain, the majority of them British-born. The 2001 Census also showed that Irish people are more likely to be employed in managerial or professional occupations than those classed as “White British”.

As a result of the Irish financial crisis, emigration from Ireland has risen significantly. Data published in June 2011 showed that Irish emigration to Britain had risen by 25 per cent to 13,920 in 2010

Link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irish_migration_to_Great_Britain

To this day, Liverpool is jokingly referred to as the second largest City in Ireland.

THE IRISH AROUND THE WORLD:

The most obvious and well known instances of Irish Emigration and travel, clearly involve the US, Canada, Britain and Australia, but they are not limited to those Countries.

The Irish have emigrated and travelled EVERYWHERE on this Globe.

It reminds me of the story a once famous mountain climber recalled, that on a trip to the Himalayas on an expedition to climb Mount Everest, he discovered an Irish Pub in Kathmandu!

We all know Irish people or have Irish friends that live ALL OVER Europe, the Middle East, Asia, South America, New Zealand, China and Russia.

CONCLUSION:

Are these people ‘Irish’? Are their children ‘Irish’? Are their grand-children ‘Irish”? Are their great, great, great grand-children ‘Irish’?

The answer is that OF COURSE, they ALL ARE!

Their genetic coding is distinctly ‘Irish’. Their desire to be identified as “Irish’ is in most cases ESSENTIAL to their whole sense of belonging on this Earth. A sense of PLACE, a sense of ORIGIN, a sense of PRIDE.

It is true that the diaspora’s manifestation of ‘Irishness’ is often based on a ‘stereotype’ that is rooted in popular culture. The diaspora (and in particular the Irish-American’s) have been raised on a diet of ‘The Quiet Man’, ‘Lucky Charms’ and ‘Leprechauns’. It is not their fault that popular culture has led them in this direction. Their expression of ‘Irishness’ is not intended to insult and is not designed to mock the ‘native Irish’. It is well intentioned. Their physical separation from Ireland, prior to the information age, has caused some loss of understanding of the progress of modern Ireland, its high tech, bohemian and 21st Century development, but it does not lessen their feeling of Irish identity.

I think I have just proven through our history that we are a race of travelers, explorers, a race of migrants. It has always been who and what we are. We cannot help ourselves, in our desire and need to travel. It is genetic. It is not simply a case of “the times are hard and it is time to go”. Yes, there have been many occasions in our history where emigration was the only logical choice or option to survive, but not always the case. Even in good times, we ‘Irish” have emigrated and travelled.

Perhaps, Van Morrison said it best, when penning the Lyrics to his song:

“What Makes The Irish Heart Beat”

“All that trouble all that grief

That’s why I had to leave

Staying away too tong is in defeat

Why I’m singing this song

Why I’m heading back home

That’s what makes the Irish heart beat

I’m just like a hobo riding a train

I’m like a gangster living in Spain

Have to watch my back and I’m running out of time

When I roll the dice again

If lady luck will call my name

That’s what makes the Irish heart beat

Well that’s what makes it beat

When I’m standing on the street

And I’m standing underneath this Wrigley’s sign

Oh so far away from home

But I know I’ve got to roam

That’s what makes the Irish heart beat

And it was off to foreign climes

On the Piccadilly line

We were standing underneath the Wrigley’s sign

So far away from home

Well I know I’ve got to roam

That s what makes the Irish heart beat

Just like a sailor out on the foam

Any port in a storm

Where we tend to burn the candle at both ends

Down the corridors of fame

Like the spark ignites the flame

That’s what makes the Irish heart beat

But I roll the dice again

If lady luck will call my name

That s what makes the Irish heart beat

Oh, that’s what makes the Irish heart beat

That’s what makes the Irish heart beat”

To those ‘native’ Irish who refer to the Irish diaspora in derogatory terms, I would remind them not to be so hypocritical.

I ask them to examine our history to see the loyalty that the Irish diaspora have consistently held for their native land.

Many of the ‘naysayers’ own relatives/ancestors of ‘the past’, were ones who emigrated, be it by force, compulsion or design.

They did not abandon their Country as many would have you believe. They simply moved their Country with them to a new land of hope, freedom and potential prosperity.

Do not forget that many of these Irish diaspora ‘funded’ the struggle for better conditions back home for their countrymen who stayed. After the Famine, many of them paid the fares of their relatives to travel to America and the New World. Most of them sent funds home to ‘help’ make life a little easier. I still remember my grandmother receiving a yearly letter from a cousin in America (an Admiral in the US Navy no less) with some ‘cash’ in the envelope.

Do not forget that the diaspora funded the movements of the Land League, Home Rule, the IRB, the Fenians, the Irish Volunteers, the War of Independence, the Old IRA, the Civil War, and more recently (however misguided) the Provisional IRA. Those movements would not have survived, to help overcome our oppressors and achieve our Republic, without the funding and armaments provided, in particular, by the Irish-Americans.

Eamon De Valera (an Irish American) and Michael Collins both knew and understood this fact. Without the support of our diaspora, we native ‘Irish” might still be called ‘British’ to this day!

Be thankful for the Billions of Euros contributed to the Irish Economy every year by the diaspora, either coming home to connect with their roots or to simply buy Irish products.

So, in conclusion, I simply say that ANYONE who has one ‘scintilla’ or Irish DNA is ‘Irish’ (if they want to be identified as ‘Irish’), regardless of where they now call home.

I say, “wear your silly hats, wear your silly leprechaun suits, by all means dye your rivers and Guinness green,

Show your Pride in being ‘Irish’ in any way you feel, BUT …. PLEASE …… PLEASE ………. “for the love of all that is Holy and Sacred” …….

‘STOP’ ……. saying,

‘Top O’ The Mornin’ to Ya”!

(NOTE: TO PUT IT SIMPLY, NO ‘IRISH’ PERSON USES THAT PHRASE AND IT HAS IT’S ORIGINS IN A 1920/30’s HOLLYWOOD STEREOTYPE OF THE IRISH ‘FOOL’!

ALTHOUGH NOTORIOUSLY DIFFICULT TO OFFEND, MOST IRISH PEOPLE, ACTUALLY FIND IT, ‘A TAD’ OFFENSIVE!)

The author of this article is Nevan O’Shaughnessy, born and raised in Ireland. Lived in Ireland for 50 years. One of the millions of ‘Irish’, who has chosen to live elsewhere in the World (in his case the US) and now call it …. ‘HOME away from HOME’.

A ‘PROUD’ Irishman to ‘the grave’ and raising his children to be as much ‘Irish’, as they are ‘American’!!!

Nevan is the owner of Rockwell Antiques in Dallas, Texas, Specialists in Irish Antiques.

Rockwell Antiques Dallas

WEBSITE: www.rockwellantiquesdallas.com

Ph: +1 (972) 679-3309

Email: rockwellantiquesdallas@gmail.com

Copyright Rockwell Antiques Dallas and Nevan O’Shaughnessy 2025.